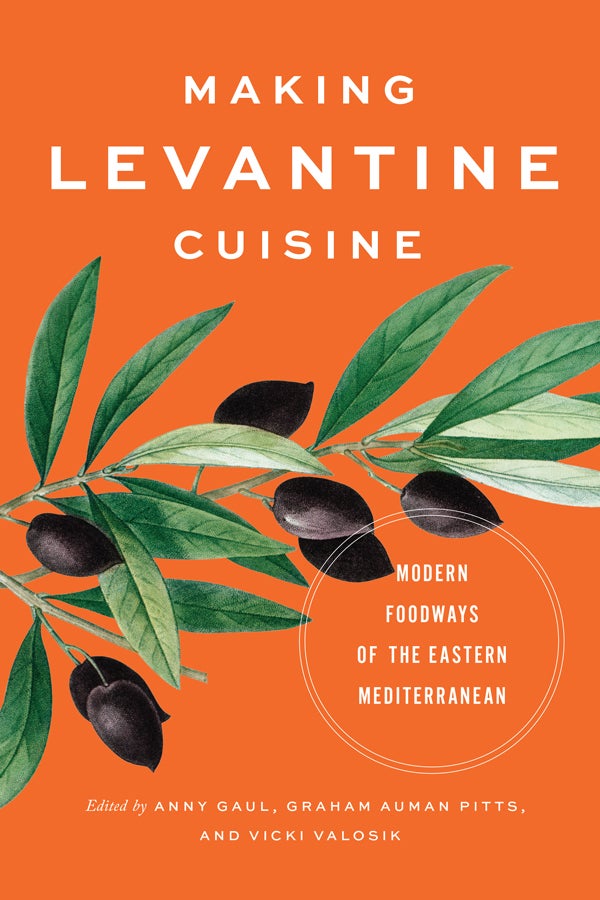

The following is an excerpt from the Introduction to Making Levantine Cuisine: Modern Foodways of the Eastern Mediterranean.

By Anny Gaul and Graham Auman Pitts.

In sight of Jerusalem’s Damascus Gate, restaurateur and cookbook author Yotam Ottolenghi tells Anthony Bourdain that the Ottoman occupation of Palestine ended “150 years” before their 2013 interview. The cameras for Bourdain’s Parts Unknown TV series then follow the pair to a falafel stand inside the Old City’s Muslim Quarter. In response to Bourdain’s query about the origin of the iconic fried chickpea dish, Ottolenghi declares, “There’s actually no answer.” As the author of several best-selling cookbooks (including Jerusalem: A Cookbook), Ottolenghi, along with his collaborator Sami Tamimi, is perhaps the most prominent chronicler of the Levant’s cuisine. However, his answers to Bourdain distort the history of Levantine food. The Ottoman occupation ended in late 1917, not even 100 years before the “Jerusalem” episode was recorded. Ottolenghi and Tamimi’s cookbook does correctly cite the date for the Ottoman withdrawal but reproduces a tired Orientalist cliché, describing the early twentieth-century city as “miserable, congested, and squalid.” The history section glosses over Zionist immigration from Europe, the signal development of modern Palestine’s history. The falafel that Zionist settlers eventually came to claim as their national food was made by Palestinians first. It belongs to a family of fritters made with fava beans, or chickpeas in the Palestinian version, that had long been shared throughout the Arab Eastern Mediterranean, from Alexandria and Port Said in Egypt to Beirut in Lebanon.

The cookbook authors also make a “leap of faith . . . that hummus will eventually bring Jerusalemites together,” yet such assumptions disregard the history of that dish and the broader progression of cultural encounters in Israel-Palestine. Historically, the appropriation of Levantine foods like hummus by European Jews has not corresponded with improving intercommunal relations but rather with the further entrenchment of Israeli colonialism. Misconceptions about one of the world’s most prominent cuisines persist, given the scarcity of scholarship on its origins.

Ottolenghi and Tamimi’s commodification of their “Jerusalem” brand is typical of the way in which the forms of dispossession essential to modern Levantine cuisine, in its different guises, have been obscured. Turkey and Israel both assembled their national cuisines from the traditions of populations marginalized in the making of those nations. In adopting Arab and Armenian dishes, Turkey’s national food culture attempted to obscure a non-Turkish past. Since Israel’s founding in 1948, the uneven and shifting attitudes within mainstream culture toward the foods of marginalized communities masked a history of violent dispossession, in the case of Palestinians, and systemic discrimination, in the case of Jewish populations who immigrated to Israel from the Arab world. Each project for a national cuisine undermines its nationalist aims by tacitly revealing a diverse past and the persistent cultural unity of a politically divided region.

In addition to ethnocentric nationalist agendas, conventional discourse has concealed the inequalities of class and gender essential to making modern Levantine cuisine. Paid and unpaid female laborers have been key to the reproduction of Levantine foodways. This modern food culture began to develop once capitalist social relations took hold in nineteenth-century Beirut. Unlike the traditional mode of production where the terms of exploitation are obvious, they remain hidden under capitalism. It is the task of critique to reveal them (Amin 1978). In centering questions of labor and inequality, this volume peels away the ideological branding that has largely defined this cuisine.

Making Levantine Cuisine is the first book-length scholarly work devoted to Levantine food and foodways. The concept of “foodways” shifts our focus beyond food itself to a framing that considers the social contexts that make food and make food meaningful––spanning from fields to markets to kitchens, factory spaces, and restaurants. Eight chapters by anthropologists, historians, and critical theorists address this gap in our knowledge of global food history and culture. From a range of disciplinary perspectives, we address several broad questions: What is Levantine cuisine, historically, culturally, and gastronomically? What is the relationship between national and regional cuisines in the Levant? How does cuisine offer a way of conceptualizing the Levant beyond its traditional national borders? How are its national and regional variants known, consumed, and discussed by those inside the region and outside of it? Can studying the region’s food and foodways help us better define or understand what constitutes “the Levant” or what counts as “Levantine” and how they came to be?

Supplementing these scholarly perspectives on what “makes” cuisine Levantine are essays and recipes that offer a glimpse into the kitchens where Levantine cuisine is made in a more tangible sense. This combination of scholarly, practical, and personal literature reflects both a feminist commitment to the validity of diverse perspectives and a conviction that as food scholars we have much to learn from matters of practice and lived experience.

The volume begins with the local and granular and gradually expands to encompass the Mediterranean and the world beyond. These accounts reveal an understanding of Levantine cuisine as an entity that has never mapped neatly onto political boundaries. They also look beyond the region to show how culinary styles most commonly known today as “Lebanese,” “Israeli,” or variants of the vaguer “Mediterranean” coalesced in the twentieth century as the product of global diasporas, modernization, and national tradition-making. Stories centered on food, in turn, recast the histories of these national communities…

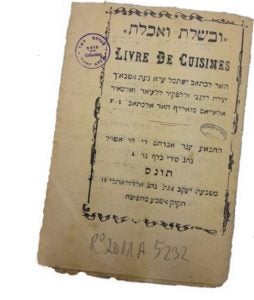

…In Jacqueline Kahanoff’s formulation, the Levant is less aptly described through the metaphor of a mosaic than as “a prism whose various facets are joined by the sharp edge of differences, each of which . . . reflects or refracts light” (qtd. in Alcalay 1993). We have assembled a dozen essays that together present an account of modern Levantine cuisine as a multifaceted entity that students, scholars, and home cooks can use to view the region from a slightly different vantage. Their authors have collected and mediated materials in Armenian, English, French, Judeo-Arabic, Hebrew, and multiple registers of Arabic and Turkish. Through collected recipes, thick description, archival research, and close readings of understudied cookbooks and restaurant menus, they present an argument for a deterritorialized understanding of Levantine cuisine.

By “deterritorialized,” we mean several things that on the surface may appear contradictory. First, this book locates Levantine cuisine beyond the fields that produced its ingredients, the places that its cooking styles first developed, and the geographical borders of a short list of nation-states in the Eastern Mediterranean. In this volume, you will find Levantine cuisine appearing in Aleppo, Beirut, and Jerusalem but also in Palestinian and Syrian kitchens in Jordan, as well as farther afield in Venezuela, the Netherlands, and the United States.

Second, by limiting our scope to the region of the Levant, we are also honing in on a specific set of environments and landscapes that produce the food we discuss. In doing so, however, we adopt a critical approach. We join the ranks of food scholars who have criticized, in the words of Kyla Wazana Tompkins, the “romanticized and insufficiently theorized attachments to ‘local’ or organic foodways, attachments that sometimes echo nativist ideological formations,” which underpin much of contemporary (and privileged) “foodie culture” (2012:2). Without losing sight of the importance of attachments to local ecologies and place to the making of Levantine cuisine, we aim to resist taking them at face value. The association of foods or ingredients with specific places is common and more often than not contains at least a kernel of truth; but it often illuminates more about who is making the association than it does about the place.

Presenting an understanding of Levantine cuisine that originates and resides within specific borders and travels beyond them produces a tension that runs throughout this book, but it is a tension that we embrace rather than seek to resolve. The culinary culture elucidated in the following chapters took shape both discursively and materially only as the geographical Levant became integrated within a global capitalist system over the course of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries––and its inhabitants left their home shores and villages. The stakes of national identification were heightened by displacement, population transfers, the fragmenting of empires, and decolonization. Industrialization reconfigured foodways and drove internal and external migration that in turn rendered a set of regional and home-cooked recipes into commercial dishes that became known from Istanbul to New York and beyond. Writing the history and present of Levantine cuisine requires placing narratives of movement and migration in conversation with renewed attachments to the local within the region itself.

To write the rhythms and sensory richness of food, past or present, always proves an elusive task. Like making kibbe or stuffing grape leaves, we believe it is a task best done collectively. [This book] is our attempt to put down in words the making of Levantine cuisine.

Dr. Anny Gaul is a MAAS alum and an assistant professor of Arabic Studies at the University of Maryland, College Park. Dr. Graham Pitts is a visiting professor at the Elliott School of International Affairs at George Washington University, as well as an adjunct visiting professor and former American Druze Foundation Fellow at CCAS. Making Levantine Cuisine: Modern Foodways of the Eastern Mediterranean was published by University of Texas Press in 2021 and edited by Anny Gaul, Graham Auman Pitts, and Vicki Valosik.

This excerpt appeared in the Winter/Spring 2022 CCAS Newsmagazine.