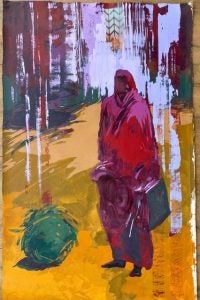

MAAS student Ingie Gohar traces the deteriorating rights of the growing Sudanese migrant community in Egypt

By Ingie Gohar

In 2004, Egypt and Sudan signed the Four Freedoms Agreement, granting Sudanese nationals the right to freedom of movement, residence, work, and property ownership in Egypt. The agreement aimed to strengthen bilateral relations and enhance cooperation between the two countries. However, Egypt has never fully implemented the agreement in practice, and the situation for Sudanese nationals has only deteriorated over time.

Following the outbreak of the current conflict in Sudan in the spring of 2023 and the sharp increase in arrivals from that country, Egypt suspended the agreement and placed new restrictions on the entry, residency, and employment of Sudanese refugees. These restrictive policies have forced many of those fleeing the war to resort to dangerous irregular migration routes, only to then encounter precarious conditions in Egypt. Egypt’s deteriorating economy has also left much of the local population struggling to make ends meet, fueling frustration against migrants as the public—and the media—searches for scapegoats.

The war, which is being fought between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), has caused mass displacement and led to a devastating humanitarian crisis. In December 2024, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) estimated that more than 12 million people in Sudan had fled their homes, with 8.8 million displaced within Sudan and 3.2 million seeking refuge in neighboring and other African countries. Egypt, given its proximity and historic ties to Sudan, has seen an estimated 1.2 million Sudanese enter the country since 2023, with “hundreds” reportedly entering daily, as of November 2024.

Despite its initial commitment to international agreements protecting refugees, the Egyptian government’s stance has shifted as economic pressures have mounted and international support has proven insufficient. In the war’s first month— April 2023—Sudanese women and girls, boys under 16, and men over 50 could enter without a visa, while the remaining male constituents were able to obtain visas relatively easily. But that June, Egypt abruptly announced that all Sudanese citizens would require visas. Wait times stretched to three months, forcing many to rely on brokers, facilitators who offer fast-track visa services but charge exorbitant fees that are unaffordable for many Sudanese.

As the situation in Sudan has deteriorated and Egypt’s restrictions further tightened, many Sudanese have been forced to turn to smugglers to cross the border into southern Egypt, a dangerous journey that puts them at risk of violence and exploitation. Moreover, Sudanese refugees are subject to widespread arbitrary arrests and deportations, which are backed by European Union funding that aims to curb migration to Europe via Egypt. In March 2024, the EU announced a €7.4 billion aid package to Egypt, most of it in the form of loans intended to boost trade and stabilize the country’s economy. The deal also includes €200 million specifically allocated for border and immigration enforcement.

Those seeking to regularize their status — that is, to obtain or renew legal residency and avoid the risk of arrest or deportation—also face a $1,000 fee introduced by Prime Ministerial Decision No. 3326 of August 2023, which targets refugees with expired residency permits or those without proper documentation. Although Egypt has repeatedly extended deadlines, the decision left many in limbo and served as a justification for periodic crackdowns.

Despite the current situation, Egypt has a long history of hosting refugees. Since Egypt’s 1954 Memorandum of Understanding with UNHCR, responsibilities such as registration, documentation, and refugee status determination have largely been managed by UNHCR. This arrangement is not uncommon, and many countries without comprehensive national asylum systems rely on UNHCR to carry out these functions in order to ensure basic protections. However, last December Egypt’s parliament rushed through a controversial asylum law that gives the government, rather than UNHCR, the power to determine refugee status, which critics argue could severely undermine refugee rights. The new law marks a first step toward “institutionalizing” Egypt’s international obligations in the area of asylum and has led to refugees being granted some basic rights, such as the ability to apply for Egyptian citizenship, for the first time. But it also imposes stricter criteria for obtaining refugee status, enforces a 45-day deadline for asylum applications, permits arbitrary detention, and includes vague criteria for revocation of status or forced returns, such as commit- ting “acts that interfere with national security or public order.” Moreover, the law restricts access to essential services and even criminalizes the unauthorized provision of assistance, such as shelter or employment, to asylum-seekers.

Even those who gain refugee status face numerous obstacles to building a stable life in Egypt, including providing education for their children. New regulations require Sudanese children to have residency permits in order to attend Egyptian schools, but at the same time, Egyptian authorities have been cracking down on secondary schools opened by the Sudanese community to fill the growing educational gap—forcing many to close. Moreover, a large proportion of those fleeing Sudan for Egypt are students or college-age youth, but those seeking to continue their education face high tuition fees, bureaucratic obstacles, and visa restrictions. Before the war, Sudanese students received a 90 percent tuition discount at Egyptian universities, but this was recently reduced to 60 percent. In addition, foreign students face additional fees of up to $2,000, making education nearly unattainable.

The entry of refugees into Egypt, coupled with their portrayal as a financial and economic burden, has fostered a climate of hostility that aligns with the country’s recent restrictive measures. The hostile rhetoric is also fueled by government media and by co- ordinated social media campaigns against refugees that call for stricter measures and divert public attention away from Egypt’s systemic economic problems.

The 2023 devaluation of the Egyptian pound worsened the situation by driving up the cost of living—for Egyptians and immigrants alike—making basic necessities unaffordable to many. To cope with these rising challenges, Sudanese refugees are creating and turning to Sudanese-led support networks and community-driven initiatives, including not only schools, but also community-based organizations (CBOs) and volunteer-run associations that provide essential services and skills-building opportunities to newcomers to facilitate their employment in Egypt. These initiatives often provide the only lifeline for Sudanese refugees, who may be overlooked by larger international organizations. A few Sudanese have also opened businesses and restaurants in Egypt, catering to the needs of their community while creating spaces for gathering, networking, building connections among the displaced, and providing jobs to asylum seekers and refugees. However, economic integration re- mains a major challenge, as many refugees struggle with having their previous work experience and educational certificates recognized, which confines them to low- skilled, underpaid work—regardless of the professional status or skilled employment they held in Sudan.

An Urgent Need for Solutions

A lasting solution for displaced Sudanese will require coordinated regional and international action, as well as a comprehensive response that ensures humanitarian aid and protection for refugees in Egypt and neighboring countries. This should include redirecting resources to grassroots initiatives that effectively ad- dress immediate challenges. Moreover, Egypt must up- hold the Four Freedoms Agreement and establish clear legal protections for Sudanese refugees. Simplifying residency procedures and access to elementary, secondary, and university education would ease burdens on displaced families, while a balanced media narrative, supported by refugee organizations, journalists, and human rights groups, is needed to counter misinformation and anti-refugee rhetoric. The United States should press for humanitarian corridors and a roadmap for peace in Sudan, while also leveraging its ties with Egypt to advocate for fairer refugee policies and fewer restrictions on Sudanese asylees. At the same time, Egypt will need international support to address the economic challenges facing both its population and the refugees it hosts.

While international aid and grassroots efforts are important, they cannot replace the need to address the root causes of war in Sudan. Above all, the international community must listen to the Sudanese people, amplify their demands, and support their aspirations for self-governance and a peaceful and just future. Only by centering their voices can the world hope to create meaningful and lasting change in Sudan. ◆

Ingie Gohar is a second-year student in the MAAS program who conducted her thesis research on the securitization and socioeconomic exclusion of Sudanese refugees in Egypt. A longer version of this article was published on January 24, 2025 by Arab Center Washington DC. Reprinted here with permission.

This article was published in the Fall 2024-Spring 2025 issue of the CCAS Newsmagazine.