Professor Killian Clarke and alum Jérémie Langlois use protest data to reveal how Sudan’s 2019 uprising unfolded—and what it can tell us about people power and state repression.

By Killian Clarke and Jérémie Langlois

From late 2018 to 2019, a largely unarmed mass movement of Sudanese protesters led to the ouster of long- time dictator Omar al-Bashir and the beginning of a transition to democracy. Though this transition was subsequently cut short by a counterrevolutionary coup, and then a collapse into civil war, the 2019 revolution nonetheless marks a watershed moment in Sudan’s history—an effort by everyday Sudanese citizens to wrest political control from entrenched authoritarian actors. At the same time, this revolution is just the latest manifestation of people power in Sudan, which has a long history of revolution, with similar uprisings ousting autocratic incumbents in 1964 and 1985.

To better understand the 2019 revolution, we collected data on the many forms of protest and political mobilization leading up to and following the overthrow of al-Bashir. The dataset includes information on when and where protests occurred, who participated, and how the state responded. It begins in mid-December 2018—when protests over escalating bread prices in the small city of Atbara escalated into direct calls for Bashir’s removal—and ends in August 2019, which marked the beginning of the formal transition to democracy. The 4,088 events we documented include protests, marches, sit-ins, roadblocks, strikes, and mass attacks. For each event, we also recorded a wide range of details about the protest itself: location, timing, number and type of participants, presence of organizations, demands, tactics, and any government response or repression. This fine-grained data offers a rich, multidimensional lens through which we were able to map the Sudanese protest movement across the full arc of the revolution.

One of the greatest challenges in collecting protest data is finding news sources that accurately and consistently provide information on these events. This is especially difficult in an authoritarian

context like Bashir’s Sudan, where few local and independent media outlets existed. Coverage by international news and wire services like AP and Reuters is insufficient, as these outlets tend to limit their reporting to larger, more violent, and urban events. To build our dataset, we therefore drew on a variety of Sudan-focused, Arabic-language sources. First, we collected events from Radio Dabanga, a Sudanese news outlet based outside the country that nevertheless provides strong on-the-ground coverage. Second, we included data from three activist-run Facebook pages that offered daily updates on demonstrations throughout much of the revolution. Finally, we reviewed several existing event catalogues and news aggregators to capture events covered in other Sudanese media outlets, such as Al- Rakoba, Al-Nilin, and the English-language Sudan Tribune. Taken together, these sources provide con- sistent and wide-ranging coverage of protests across Sudan over the full course of the uprising.

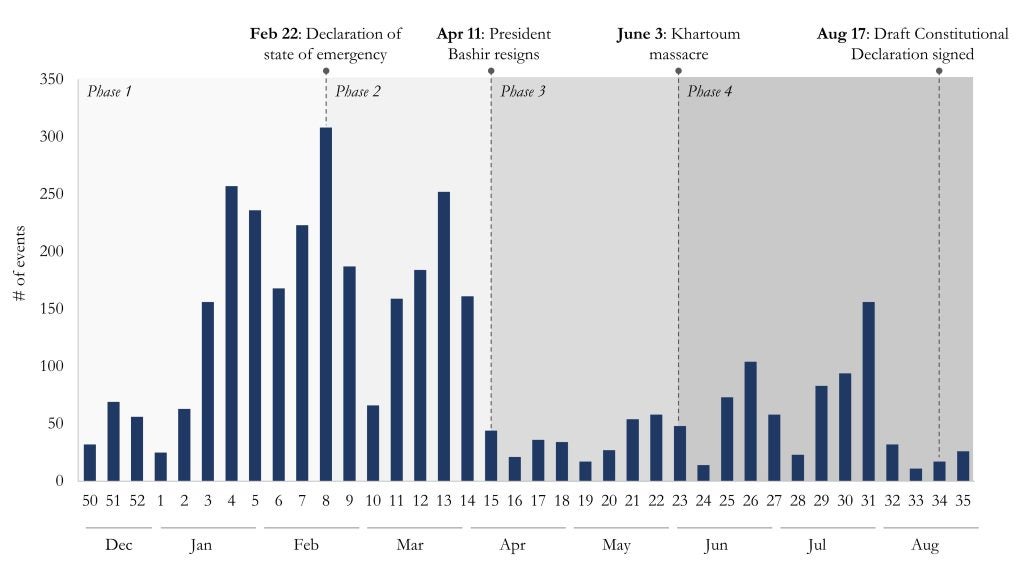

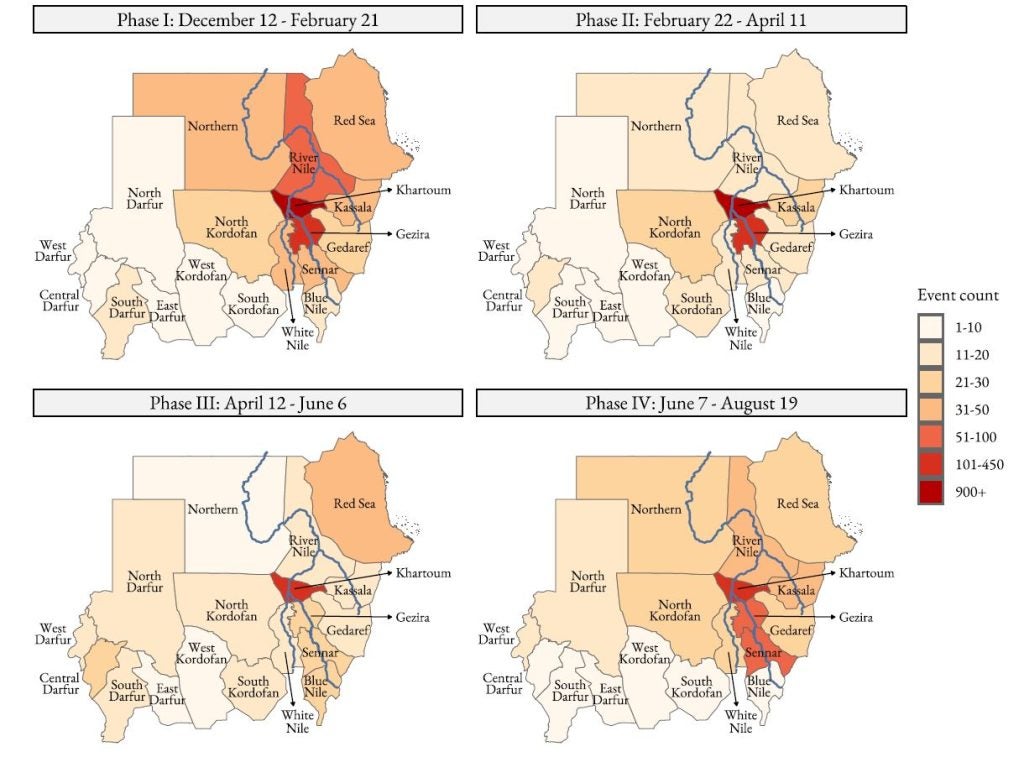

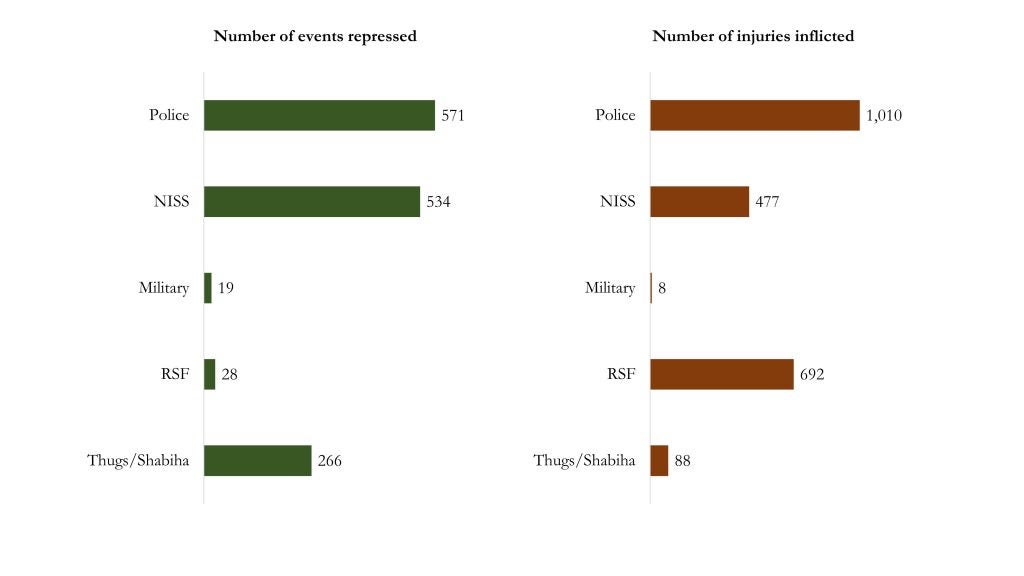

In this article, we present three descriptive figures drawn from our dataset. While our analysis is still ongoing, these visual overviews offer important insights into how the revolution unfolded—both in terms of protest timing and geographic spread, as well as the state’s response to the protests. Figure 1 depicts weekly protest counts from December 2018 to August 2019, illustrating how mobilization ebbed and flowed over time. Figure 2 adds a spatial dimension, using geocoded data to show where protests occurred across Sudan’s 18 governorates or wilayas. To highlight broad trends, we divide the revolution into four phases, which are demarcated in Figure 1 and represented in the four paneled maps in Figure 2. In Figure 3, we provide a summary of the scale and kinds of repression committed by coercive actors in response to the protests.

Protests across Time and Space

In the first phase of the revolution, spanning from mid-December to mid-February, protests were concentrated in the “near-periphery”— the Nile corridor, including Khartoum, and the Arabic- speaking Northern and Red Sea provinces—as illustrated in he top left quadrant of Figure 2. Although demonstrations had spread nationwide by late December, they intensified around January 17, which was also when the Sudanese Professionals Association (SPA)—an umbrella group of 17 trade unions formed in 2012 during the Arab Uprisings— organized its first official protests. That week, SPA organizers reported that the National Intelligence and Security Service (NISS) agents had “unleashed a campaign of thuggery–the biggest show of intimidation to date.”(*1)

The second phase (Fig. 2, top right) began on February 22 when a state of emergency was declared, marking a turning point in the regime’s response to protests. Bashir replaced governors and top officials with military officers, and internet blackouts became more frequent. After an initial spike in protest activity, the number of demon- strations dipped in early March. But momentum rebounded later that month after a series of demon- strations successfully “shamed” the regime into freeing hundreds of women who had been detained during protests. On April 6, activists launched a mass sit‐in outside the army headquarters in Khartoum. After five days of sustained demonstrations against the military, General Ahmed Ibn Awuf announced Bashir’s ouster on April 11. This phase shows a clear consolidation of protest activity in the capital.

The third phase, following Bashir’s fall, saw fewer protests overall as opposition leaders began negotiating with the Transitional Military Council (TMC). Still, the SPA continued demanding full civilian rule and organizing protests, including sustaining the weeks-long sit-in at the army headquarters that had begun on April 6. As the

map (Fig. 2, bottom left) illustrates, mobilization persisted throughout the country, with nearly all of Sudan’s 18 states seeing at least a dozen protests. The geographic reach of these ongoing protests, including sit-ins at regional army headquarters in several wilayas, suggests a dynamic process of coalition-building within the movement, even as the count of protest events dropped.

On June 3rd, following a week of reports of escalating state violence, military and security forces cleared the sit-in at the national army headquarters in Khartoum with tear gas, sound bombs, and vehi- cles. They killed at least 100 people and committed widespread atrocities, including the rape of at least 70 people and the injury of hundreds more. The massacre initiated a broader campaign of state and parastate violence across the country, which lasted just over a week but included mass murders and extrajudicial killings, rape, assault, pillaging, and the intimidation of civilians and striking workers.(*2)

Yet this brutal crackdown sparked a powerful backlash. Weekly protests soared, and organizational solidarity strengthened in response to the violence. The fourth phase (Fig. 2, bottom right), began on June 7, with the first major SPA-led protest after the massacre. In response to the SPA’s call for “complete civil disobedience and open political strike,” weekly protests throughout the summer soared, reaching levels that had not been seen since Bashir’s ouster. This sustained mobilization gave opposition leaders critical leverage in negotiations with the military. On August 17, Sudan formally began a transition to civilian rule following a power-sharing agreement between the military and the Forces for Freedom and Change (FFC), a broad coalition of opposition groups formed earlier that year.

Agents of Repression

Authoritarian regimes rarely give up power without a fight, and Bashir’s regime responded to the revolution with harsh crackdowns and violent repression. More than 250 people were killed—almost all by the state—and thousands more were injured. The most brutal crackdown was the June 3 Khartoum massacre described above, but there were many oth- er instances of repression, particularly in the early stages of the revolution before Bashir stepped down.

Our dataset allows us to track not only when and where repression occurred, but also who was re- sponsible. In addition to recording both the severity of repression (e.g., tear gas versus live ammunition) and the number of casualties for each event, we also tracked which actors were involved. Figure 3 pro- vides a summary of repression committed by each of the five major actors: the police; the National Intelligence and Security Service (NISS), a powerful standalone security and intelligence agency; the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF); the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), a paramilitary force that evolved from the Janjaweed militias in Darfur; and unnamed state-backed thugs, known in Arabic as shabiha or beltegeyya. The figure’s left panel shows how many protest events were repressed by each of these actors. The right panel displays the total number of injuries they inflicted during protests.

The figure sheds light on how coercive authority was distributed within Bashir’s regime. Most of the repression was carried out by the police and the NISS, which were also involved in the largest number of protest crackdowns. Strikingly, the military itself played only a limited role in direct repression, despite being one of the regime’s most powerful actors. In fact, it was senior military leaders who ultimately forced Bashir from power and sidelined Salah Gosh, the reviled head of the NISS. These same generals went on to form a junta called the Transitional Military Council, assuming direct control of the country until the transition agreement with revolutionary forces was signed in August 2019.

Despite its power, the military largely refrained from deploying its own forces against protesters. This was likely a strategic choice, as direct involve- ment in repression could have damaged its national standing, so the generals instead asserted their authority through other coercive actors. Like other autocratic regimes in the region, Bashir’s government relied heavily on the use of state-backed thugs to supplement its main agents of repression—the police and NISS. Because these thugs had no official role in the regime, they provided the government a degree of anonymity and deniability. As the right panel reveals, however, these thugs were not involved in the most violent acts. Their primary function was to harass and intimidate protesters, spreading fear and uncertainty within the protest movement.

The final coercive actor in our data is the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), a paramilitary group led by Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, who is also known as Hemedti. Formed in 2013, the RSF grew out of the Janjaweed militias that committed war crimes in Darfur during the 2000s. For Bashir, the RSF served as a kind of praetorian guard, protecting him from threats within his own security establish- ment. Although the RSF was not involved in as many protest crackdowns as the police or NISS, its actions were far more violent. As the figure shows, the RSF was involved in some of the most brutal repression during the revolution, including the June 3 Khartoum massacre.

Conclusion

Using our original event dataset, we have mapped the arc of Sudan’s remarkable revolutionary movement. The data traces how protests rose and fell over time—centralizing in the capital before returning to the periphery—and how they escalated and receded in response to both activist interven- tions and the responses of the state. Together, these patterns reveal the dynamic and iterative nature of revolution, showing how a movement that began with a scattered series of protests outside the capital ultimately toppled a long-standing dictator and set the stage for a transition to democracy. ◆

Dr. Killian Clarke is a political scientist and an assistant professor in the School of Foreign Service, affiliated with CCAS. Jérémie Langlois is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Political Science at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and a MAAS alum.

*1 Sudan’s Unfinished Democracy: The Promise and Betrayal of a People’s Revolution (Oxford University Press, 2022, p. 30)

*2 Press Release from the Sudanese Professionals Association, “Complete civil disobedience and an open political strike to prevent chaos” ( June 4, 2019)

This article was published in the Fall 2024-Spring 2025 Issue of the CCAS Newsmagazine.