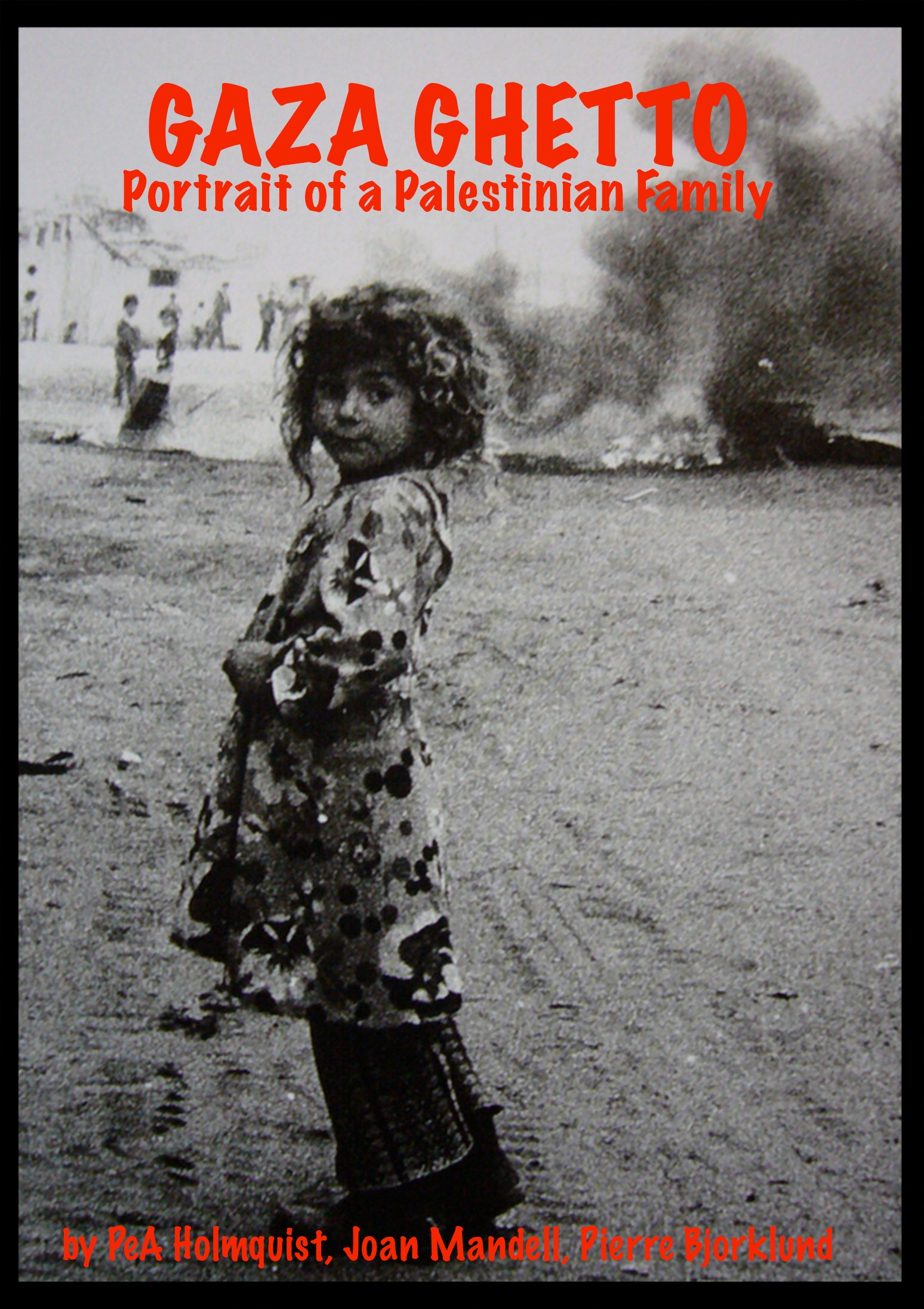

The first documentary on Gaza, co-produced by CCAS Professor Joan Mandell forty years ago, provides an historical record of daily life under occupation.

By Shifaa Alsairafi

Gathering for Alarba’een, a day of remembrance when mourners come together on the 40th day after the death of a loved one or prominent figure, is a common practice in much of the Arab world. The 40th anniversary of the groundbreaking film Gaza Ghetto: Portrait of a Palestinian Family, 1948-84, which was co-directed by CCAS Professor Joan Mandell and was the first documentary produced about Gaza, was accompanied by a similarly solemn tone—not only because the neighborhoods depicted in the film have been destroyed since the documentary was released in 1984 but also because the situation in Gaza has grown exponentially worse in recent decades.

Gaza Ghetto is set in Jabalia, which—along with the entire Gaza Strip—came under Israeli occupation following the 1967 war, and by the 1980s had become home to the largest refugee camp in the occupied Palestinian territories. Mandell and her co-directors chose Jabalia as the primary site for the documentary not only because of its size and historical importance, but also because of her familiarity with many intellectuals and artists living there who could narrate their story. “Jabalia had a vibrant life of arts and activism, and many people who wanted to share it,” recalls Mandell. Although the film includes interviews with many Jabalia residents, its producers decided to center the story around an individual family so that they could document daily life under occupation. They ultimately selected the family of Abu el-Adel because of the family’s openness and ability to articulate their own experiences as part of a collective story. Indeed, the personal stories narrated by Abu el-Adel, his daughter Itidhal and son-in-law Mustafa, were representative of the tragedies facing thousands of Palestinians and the mass dispossession forced upon them by the Israeli state. Mandell recalls that Itidhal and her daughter Ra’ida—both strong female figures—were a major reason she was drawn to portray this family. The film opens with Itidhal confronting the Israeli settlers who live in a town that displaced her father’s village and includes scenes of Itidhal caring for her six children while husband Mustafa works the nightshift, as well as sharing the story of how her mother died in childbirth when Israeli soldiers would not allow an ambulance to reach her during a camp lockdown.

The film chronicles life in Jabalia beyond the Abu el-Adel family, depicting friends and neighbors coming together to share their stories and discuss the hardships of the occupation. Palestinian voices are also juxtaposed throughout the film with those of Israeli soldiers on foot patrol and government officials directly responsible for the administration of the military occupation. In their interviews, those with boots on the ground express dismissal of Palestinian lives and show their lack of concern for the gravity of the dispossession faced by the people whose lives they are policing. Through this dichotomy between the Abu el-Adel family’s self-awareness and strength, and the dismissive attitude of Israeli soldiers and settlers, viewers get a glimpse into the dichotomous existence of the colonizer and the colonized.

Although Mandell had experience as a journalist, she didn’t set out to be a filmmaker. During college, she worked as a photographer and editor-in-chief of her university’s daily newspaper, and later as an editor at MERIP Middle East Reports. In the early 1980s, she accepted a job as a journalist for Al-Fajr, an English-language weekly newspaper based in East Jerusalem that was trying to expose Palestinian life under occupation to the West—particularly to the United States. Many articles she wrote, however, never saw the light of day, as the newspaper was censored by the Israeli government. Mandell began thinking about other ways to share the stories and interviews she was collecting, including potentially writing a book, when an unexpected opportunity came along—in the form of Swedish cinematographer and director PeA Holmquist. Holmquist had secured funds from Swedish arts and government sources to produce a feature film about Gaza, but as a newcomer to the area, he needed the help of someone with on-the-ground experience and connections. Mandell had both, along with Arabic language skills and the carefully built trust of local communities. She says she found Holmquist to be a “determined and dedicated chronicler, with a penchant for representing stories of disenfranchised people with utmost respect,” and agreed to co-direct the film, with the hopes that it would be an effective way to carry Palestinian voices from Gaza to the West.

For Mandell, who now teaches oral history and documentary filmmaking at CCAS, producing Gaza Ghetto was not just about gathering facts and presenting them on screen—it was also about combining those facts with narrative. Even forty years ago, she says, it was evident that Palestinians were not allowed to have a narrative, let alone share it with the world. At the same time, narrative—or the human element—is what galvanizes audiences and brings about action. “The film is just one piece of the puzzle,” explained Mandell. “It is the audience that sees it and the characters depicted within it that complete the puzzle.” Mandell felt it was critical that the film depict a rich spectrum of life in Gaza—not only the harsh realities of occupation but also the resilience of those living under it—and show that Jabalia was “a place where people celebrate first love, children play and go to school, and inspiration and poetry are alive.”

Gaza Ghetto poignantly demonstrates the rootedness of Palestinians to their lands, but this is sadly an image that Israel would like to erase from both distant and recent memory. In the forty years since Gaza Ghetto was produced, the film has become not only an historical archive of what once was, but also a study of the conditions that have led to the present moment. The continued realities faced by those in the documentary—many of whom Mandell has stayed in close contact with over the years—as well as new generations of Palestinians in Gaza, make the film difficult to revisit, Mandell says: “As a filmmaker and a friend [of the families depicted in the film], I carry photographs in my brain of the places and the people. I can see the buildings and the colors of the homes where I spent so much time, and to know that Israel destroyed so much of it is heartbreaking.”

Today, with the vitality of the internet, there is more information available about life under occupation in Gaza, and Palestinians have become their own international journalists, photographers, and filmmakers as they share the atrocities Israel continues to commit against them. Even so, Palestinian voices often remain silenced, even in the West, which has long held sacred the value of free speech, as Israel and its supporters shut down any voices of dissent. For this reason, it is all the more important to get films like Gaza Ghetto out of the archives—as CCAS did in January when it hosted a screening of the film followed by a discussion with Mandell. As an historic document that has recorded and preserved the personal narratives of Palestinians, as well as the atrocities committed against them, Gaza Ghetto has become both an artifact and a tool of resistance—one that helps us understand both the precarity and persistence of the Palestinian situation in Gaza and its persistence in Palestinian life.

Shifaa Alsairafi, originally from Bahrain, is a second-year student in the MAAS program.

This article was published in the Fall 2023-Spring 2024 issue of the CCAS Newsmagazine.