By Antonio Tahhan

Molokhia—an iconic Middle Eastern and North African soup—can be notoriously slimy. But when I lived in Aleppo, my aunt taught me three tricks to keep the slime at bay: first, leave the molokhia leaves whole (as opposed to chopped); second, squeeze a lemon over the leaves as soon as you add them to the pot; and third, do not overcook them. “This is how we cook molokhia,” my aunt said. The “we” was vague. Did she mean Aleppans? Other Syrians?

“Egyptians—they make it the slimy way,” she added, raising a skeptical eyebrow.

This led me to wonder: is there such a thing as a “Syrian molokhia” distinct from an “Egyptian molokhia”? In what ways does this dish unite, but also cut through, imagined national categories, in the Arab world and beyond?

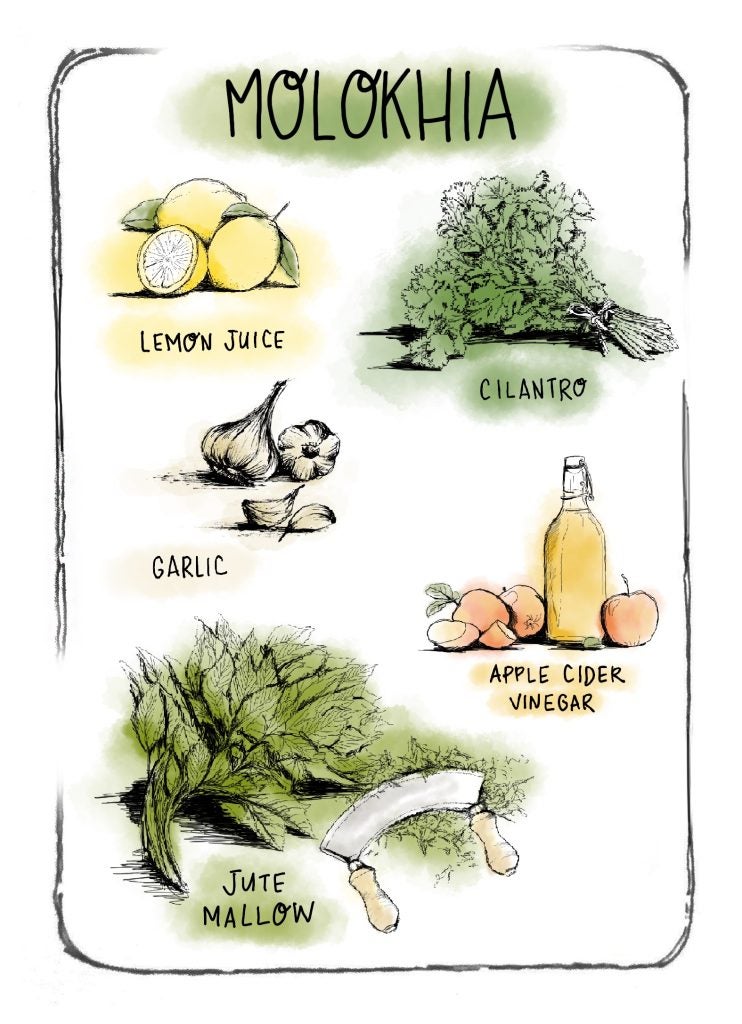

Molokhia, the dish, is made from a spinach-like plant of the same name (jute mallow in English). According to acclaimed food writer Claudia Roden, its lineage can be traced to the pharaohs of Ancient Egypt. The molokhia plant belongs to the same botanical family as okra, malvaceae. Similar to okra, molokhia thickens as it cooks. Once stewed, its leaves take on a silky, almost butter-like, texture that melts in your mouth and a flavor vaguely reminiscent of slow-cooked collard greens.

Among Arabs, molokhia is considered homey—the epitome of comfort foods. Yet unlike hummus, falafel, and tabbouleh, molokhia rarely makes it onto menus outside the Arab world. Its texture makes it a divisive dish—people either love it or hate it. The first time I had molokhia was at my aunt’s house in Syria. My mom and grandmother didn’t care for the texture, so molokhia never made an appearance on our Syrian-American dining table. For me, the flavors were heavenly.

When I returned to the U.S. from Aleppo, I was excited to make molokhia for my friends in Baltimore. I prepared it the way my aunt taught me, the Aleppan way. I started with whole, dried molokhia leaves that I reconstituted in hot water. I rinsed and drained the leaves thoroughly. Then, I sauteed an entire head of minced garlic with freshly ground coriander in a pool of earthy olive oil. Once my entire house smelled like garlic, I added the rinsed molokhia leaves and immediately doused them with freshly squeezed lemon juice. After the leaves cooked for a few seconds, I added homemade chicken broth to create a soup-like consistency. I served the molokhia alongside fluffed vermicelli rice and a big bowl of zesty, quick-pickled onions. My aunt would have been proud.

My friends rang the doorbell.

The controversy began when I pulled spoons out for everyone. My friend Elaine, whose family hails from Nazareth, felt personally attacked. “Spoons?” she asked indignantly. I responded, matter of factly, “How else do you eat molokhia?” It turns out Elaine eats hers with a fork. Her Palestinian family’s preparation is less soupy and verges on a thick stew served over rice.

Then came the issue of condiments. My favorite part of molokhia is that zing that comes from the quick-pickled onions steeped in apple cider vinegar. I make sure to scoop a bit of onions with every bite! Cedric, our friend from Beirut, agreed. Elaine, however, sided with our Egyptian friend Tamer, who prefers freshly squeezed lemons and no onions. When Tamer realized the molokhia leaves were whole, he gasped! In Cairo, molokhia leaves get chopped finely with a mezzaluna, a curved blade held together by two handles. This yields that signature gooey texture that Cairenes adore. At least Elaine and I agreed that the leaves should remain whole. We spent most of that dinner arguing (in the most loving of ways) in favor of our own preparations.

With the question of who prepares the best molokhia still looming, I designed an extensive twenty-question online survey. My friends helped me translate and offer the survey in five languages: Arabic, English, French, Portuguese, and Spanish. My hope was to use molokhia as a lens for exploring categories of national identity as my mind kept going back to the Syrian “we” in my aunt’s preparation.

I wanted to represent the data visually, so I asked participants to share the city and country where they are based. I also asked them to describe their heritage in as much detail as they felt comfortable. I then created a series of questions intended to single out defining characteristics of individual preparations: cut of the leaves, consistency of the soup, and spiciness, among other questions. I concluded the survey with a qualitative question about what molokhia means for each respondent. This allowed me to capture some of the affective qualities of this iconic dish, something cannot be conveyed through quantitative data. The survey went viral, and I ended up with more than eight hundred responses from across the Arab world and the diaspora: from Bolivia and Colombia to Kenya and Senegal. From Canada and Europe to the United States. One participant from Syria wrote:

Eating mloukheyye as I described here is Syria[n], my grandmother made it this way, my mother and even now my brother and my wife follow this same method. It seems like a unique method that only Syrians use. This seemingly unique method with the associated smell and flavor feels like home, like tradition, like family.

The connection to national pride is a recurring theme in many of the responses. At the same time, the data also suggests a more fluid reality, one that transcends national boundaries.

In the thirteenth century Syrian cookbook, Kitab al-Wusla ila al-Habib, there are four different preparations of molokhia, all of which call for meatballs, which is almost unheard of in contemporary preparations of molokhia. Most of the medieval preparations of molokhia also incorporate the use of tail fat, suggesting that lamb was a common choice of meat. Of the more than eight hundred respondents, only nine said they serve their molokhia with meatballs. By contrast, 89% said they use whole chunks of meat. Additionally, 76% specified that they use chicken.

There is a contemporary recipe for molokhia with meatballs in Sami Tamimi’s latest cookbook, Falastin. In an interview with the renowned chef, he explained that the inspiration for using meatballs was to offer a spin on the typical molokhia, served alongside chicken, “without losing the delicious flavors of the original dish.” He also said he wanted to make the dish look “more appealing” to people who didn’t grow up eating molokhia. This example illustrates not only how flavors and preparations change over time, but also how a technique from the past can re-emerge as a fresh take on a classic dish, more than 700 years later.

Nostalgia is another overarching theme in the survey responses, particularly among diaspora communities trying to recreate familiar flavors of home. A Palestinian respondent living in Michigan commented, “When we came to this country Molokai was not available. We used to wait for the packages from our grandmother in Ramallah. An exciting time in 1955.” The anticipation of molokhia care packages captures the longing to reimagine a homeland from the outside. A Lebanese-Syrian of Armenian descent living in Zürich, was willing to go even a step further. She prepares molokhia using spinach or Swiss chard, a completely different family of dark leafy greens, as the primary ingredient.

These responses from diaspora communities call into question: at what point do variations of molokhia stop being molokhia? This question becomes blurrier, or more subjective, depending on the availability of ingredients. In the United States, and most places outside the Arab world, it is difficult to come by fresh molokhia leaves. Some in the diaspora, like my friend Elaine’s parents from Nazareth, have resorted to growing their own molokhia leaves in their Oklahoma City backyard. Others have to be more flexible, or perhaps creative, in how they conceptualize molokhia. While some may argue that these more creative interpretations of molokhia are “inauthentic,” I cannot help but accept them as just the latest in a long history of varying iterations of molokhia—and not just in the Arab world.

Molokhia, the plant, exists in many cultures outside the Arab or Middle Eastern region. One respondent who identifies as Kuwaiti-Japanese of Yemeni-Indian ancestry commented how her Japanese mother prepares a slightly different version of the same dish:

My mom always made molokhiya (moroheyya in Japanese) soup growing up. She would also hand chop it to extract the sliminess to eat with somen noodles. We always grew it in our gardens in Kuwait or in Spain. The first time I cooked it myself was postpartum when I was trying to feed myself healthy food while tending to a baby.

ollaboration with Tah-

han’s research. View more of Hamidi’s art

on Instagram at @madebysaba.

In Vietnam, molokhia leaves are referred to by a completely different name, Rau Đay Xanh. They’re called saluyot in the Philippines. In Benin, molokhia leaves are used to make a similar stew known as crin-crin.

If we zoom into the survey data, we might be tempted to see a huge difference between Egyptian chopped and Syrian whole-leaf molokhia—a difference seemingly worthy of table-top battles between spoons and forks, or lemon and vinegar. But zoom out just a little, and these differences begin to blur. In some diaspora communities, we see prime ingredients replaced or grown on foreign soil that nurtures unique characteristics (terroir). Zoom out even further, perhaps to another century, and we see that medieval iterations of molokhia meatballs reemerge in glossy, twenty-first century contemporary Palestinian cookbooks.

The flavors of my own molokhia have morphed since I came back from Syria. Inspired by the variations I encountered through my survey (and all those table-top battles with friends), I have done something I was frankly scared to do. I stepped away from everything I knew molokhia to represent about my family and my Syrian heritage … I’ve experimented.

My aunt would be shocked to know that I don’t use dried molokhia leaves anymore. I pick up packages of frozen molokhia from my local Arab-American grocery store. I no longer religiously stick to dried coriander, the way she taught me. I’ve adopted Elaine’s suggestion to add freshly chopped cilantro. I no longer just do the quick-pickled onions on the side. I’ve started following a medieval technique that incorporates the smokey pulp of char-broiled onions into the base of my molokhia.

I’m not saying that anything can be molokhia. But what I’ve realized is that part of what makes molokhia “molokhia” is its variation. Adapting recipes with local ingredients, lacing elements of the past with the present, and carving out new traditions and stories through food is part of a dish’s shared history. There is no such thing as a single authentic molokhia, but rather, many molokhias that have connected people through generations and geographies.

Antonio Tahhan is a Syrian-American writer interested in the intersection of food, culture, and identity. He is graduating from the MAAS program in May 2022. If you’d like to take his mulokhia survey, you can find it at bit.ly/molokhia-survey

This article first appeared in the Winter/Spring 2022 CCAS Newsmagazine.