CCAS faculty, students, and alums reflect on how the study of gender has impacted their learning, research, teaching, and field work.

Judith Tucker

Judith Tucker

Professor of History and former CCAS Director

When I first arrived at Georgetown over 35 years ago, I had little inkling that CCAS was about to carve out a special place for itself in women’s and gender studies. I was a women’s historian, eager to integrate women’s experiences into the history of the Middle East in my classroom, but there wasn’t much to work with. Women’s history was still in its infancy when it came to the region, and there was almost nothing to draw on in terms of scholarly sources based on solid research. I assigned a few articles I found here and there in order to eke out a “women’s week” each semester, but I couldn’t imagine how to mount an entire course on women’s and gender issues. Even early on, however, the idea that gender was important was wafting around CCAS. The Center’s annual symposium in 1986 focused on Arab women and brought together scholars from the U.S. and the Arab world—virtually all women as I recall—who worked in a variety of disciplines and presented cutting edge research. And our male colleagues also came onboard: Hisham Sharabi, one of the Center’s founders, published his Neopatriarchy: A Theory of Distorted Change in Arab Society in 1988 in which he argued that patriarchal structures haunted the Arab world and blocked authentic change.

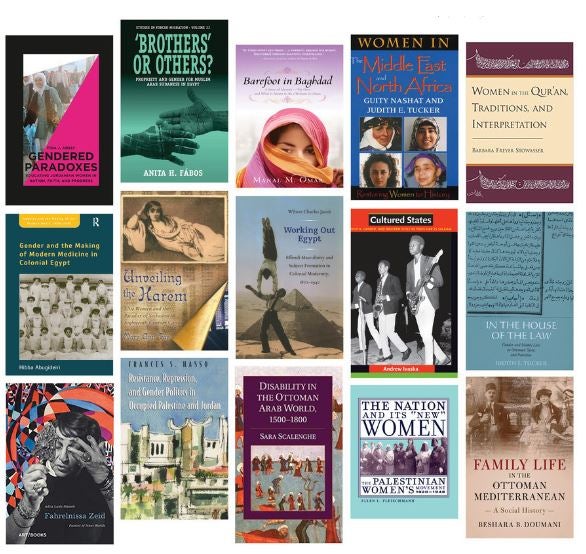

And then, in the 1990s, CCAS began to really hit its stride. Professor Barbara Stowasser started to teach a course on women in the Qur’an, and published her pioneering book on the subject in 1994. I added courses on gender and empire in the Middle East, and Islamic law and gender. And a number of MAAS students from the late 1980s and 1990s embraced the study of women and gender and went on to earn PhDs at Georgetown and elsewhere, and then played a central role in developing the field. I have room to mention only a few of the pioneers: Mary Ann Fay who changed our views of the harem and seclusion, Ellen Fleischmann who wrote the first English-language history of the Palestinian women’s movement, Wilson Jacob who set a new course in the study of Egyptian nationalism with his book on masculinity.

Over the course of the following two decades, the addition of Professor Fida Adely to the faculty strengthened our teaching on gender issues immeasurably, and we were able to develop a women and gender concentration. MAAS students continued to engage with the field and bring the gender lens to bear on a variety of subjects. As the field of women’s and gender studies in the Arab World has matured, MAAS graduates have led the way in integrating gender into the study of a wide array of subjects—disability, literacy, war, law, development, and migration to mention a few. A number of these graduates are represented in the pages of this newsletter, and it is a source of great satisfaction to note that many more might have contributed if space allowed.

We have come such a long way. Now I can teach a large undergraduate class on the history of women and gender in the Middle East and face no difficulty in finding splendid scholarly work to assign, much of it written by colleagues who once studied in the MAAS program.

Dr. Judith Tucker is Professor of History at CCAS, former Director of the Master of Arts in Arab Studies Program, former Editor of the International Journal of Middle East Studies, and President-elect of the Middle East Studies Association. She is the author of many publications on the history of women and gender in the Arab world, including Women in 19th Century Egypt (Cambridge University Press, 1985), In the House of the Law: Gender and Islamic Law in Ottoman Syria and Palestine (California University Press, 1998), Women, Family, and Gender in Islamic Law (Cambridge University Press, 2008), and co-author of Women in the Middle East and North Africa: Restoring Women to History (Indiana University Press, 1999).

Diogo Bercito

Diogo Bercito

MAAS ‘20

During my graduate studies at MAAS, I have taken three courses on topics directly related to gender: “Gender and Empire in the Middle East,” “Women and Gender in the Arab World,” and “Arab Feminism Through Literature.” I learned through these courses, for example, about how empires regulated women’s bodies to exert power in colonized territories or how particular Arab writers raised awareness of gender inequality through their work. However, regardless of the specific content of these classes, the important academic leap for me happened more in terms of learning new questions to ask in my research. This is, I believe, the result of exposure to different theoretical frameworks, which has helped me learn to see the same research object from different perspectives. For example, in my writings about Arab migration to Brazil, these classes prompted me to dig into my sources to find the answers to questions like “How did gender influence the decision to migrate?” “How did it condition the experience?” or “How did the act of migrating impact gender norms?” In a particular paper I wrote for a class, I analyzed the case of an Arab migrant in São Paulo and her writings on the role of Arab women in the diaspora. Although I knew about her story and had access to her documents, I would not have known which questions to ask until I took these courses. Without them, I would be missing a valuable opportunity to pursue more intersectional approaches in my work, taking gender into consideration along with class and race.

Diogo Bercito is a Brazilian journalist specializing in the Middle East and has covered the 2013 Egyptian coup, the 2014 Gaza war, and the ongoing conflicts in Syria, Iraq, and Yemen. He graduated in May from the MAAS program, where he developed a research focus on Arab migration to Latin America.

Alexandra Murray

Alexandra Murray

MAAS ‘20

When I applied to CCAS I knew I wanted to study women and gender. During my undergraduate program, where I studied international relations, the only exposure I had to these themes was through a class called “Gender and Terrorism.” Thankfully, it approached the topic from a critical feminist perspective, but learning about women in the MENA region only from the context of terrorism still didn’t sit well with me. I applied to the MAAS program because I wanted to learn about women and gender in the Middle East beyond the context of violence and politics. My time at CCAS has led me to a breadth of research I never would have discovered had I continued studying politics—from gender and sexuality to film and television studies. In this sense, the MAAS program has helped me winnow down my interests from the broader “women and gender” to find what I really love studying: cultural production and the various intersections of gender and orientalism within it. I am currently researching the emergence of gendered and oriental-ist tropes of Arabs in the early Hollywood era and the transnational flow of such tropes across different national film industries. As part of this project, I have been mapping the gendered and orientalist representations in the 1919 novel The Sheik, and its 1921 film adaptation, and how they fit in with Hollywood representations of Arabs at the time. MAAS has shaped my research in innumerable ways: introducing me to gender studies in anthropology and history, teaching me about gender from the lived experiences of men and women in different contexts within the Middle East, and paying strong attention to the theoretical background of these discussions. All of these factors have helped make me a stronger researcher in both Arab studies and media studies.

Alexandra Murray graduated in May from the MAAS program with a concentration in women and gender issues. She holds an M.A. in Arabic and International Relations from the University of St Andrews and is a recipient of the Jack G. Shaheen Exploratory Research Grant at the Hagop Kevorkian Center for Near Eastern Studies and the Asian/Pacific/American Institute at New York University for 2020.

Mahdi Zaidan

Mahdi Zaidan

MAAS ‘18

Focusing on gender and sexuality at MAAS was a fascinating way to learn how to tie seemingly “cultural” issues to larger historical and economic narratives. Problems that are often attributed to vague concepts like patriarchal culture or masculinity were studied at MAAS with rigorous reference to the particularities of the economic policies and sociohistorical structures in the region.

One pertinent example of this was Dr. Fida Adely’s course on development. The course largely focused on training students to analyze development narratives and rhetoric written about the Arab world. Instead of applying simplistic explanations like the culture of masculinity or tradition to themes such as women’s economic inequality, the course showcased how employment is a complex issue that is contingent upon economic policies of austerity, expansion and decline of state sectors, as well as the peculiar nature of the oil economy in the Middle East. Explanations for social issues were thus always underpinned by a deep understanding of local context. The paper I wrote for this class was on sex work in Lebanon. In analyzing the labor market and the sociological reality of women’s employment opportunities rather than focusing on vague ideas of morality or culturalism, I was able to understand the link between larger socioeconomic issues and the seemingly micro problem of sex work.

For my thesis at MAAS— “We Live in the Shadows”—I explored the themes of identity formation, socioeconomic precarity, and activism among LGBT migrants in Lebanon and Athens. My approach, again inspired by what I learned in my courses, was to historicize and complicate shallow narratives of homophobia and cultural descriptions of the region. As a result, a thesis that was originally about LGBT activism and identity ended up also exploring the history of sectarianism in the Levant, its relationship to political economy and the family, and how these phenomena could do more to explain homophobia in the region than a simple diagnosis on the premise of tradition or culture.

Mahdi Zaidan graduated from the MAAS program in 2018. He is currently pursuing a second masters in social anthropology at Cam-bridge University, where he is focusing on urban ecology and environmental activism. He hopes to begin a PhD program in London next year.

Wilson Chacko Jacob

Wilson Chacko Jacob

MAAS ‘95

I was very pleased when I received an invitation to contribute a short reflection on the role gender plays in my work as a historian and scholar. As an alumnus of MAAS, a program that one can truly be proud of, I am honored

to share a few thoughts. During my years at Georgetown, two brilliant scholars taught me to think about gender in relation to the Arab World, South Asia, and the postcolonial in general: Judith Tucker and Lalitha Gopalan. Through their historical and critical approaches to gender, I learned to think with and against a category that did not solely ensue from particular identities—yet could shape those identities.

The demonstration of this doubled role for gender—as an analytical concept and as an identity—became the object of my doctoral research and culminated in my first book, Working Out Egypt (see page 8). Gender conceived as irreducible to biologically given male or female bodies opens up the possibility of thinking, for example, about masculinity as a socially and historically constituted set of performances. Those entangled performances—of self-writing, dress, sports, association, embodied sovereignty—are what I pursued in my research in order to think more critically about the political and ethical limits of what I had seen as a globally unfolding colonial modernity (1870s-1930s) that compelled different groups to (re)organize themselves as self-determining national bodies. Regarding gender as performance opened up new vistas onto the formation and persistence of masculinist hierarchies of various scales: global, imperial, national, and so on. For example, I was able to trace starkly divergent views on the burgeoning international Olympic movement—from colonial officials, royalists, nationalists, athletes and fans. On the one hand, that global stage of physical performance could be imagined as a symbolic site for the fulfillment of national aspirations (self-determination in a cultural register, so to speak) and hence held obvious political implications that imperialists and internationalists all felt needed to be regulated. On the other hand, individual athletes from Egypt did not simply imagine the stage as symbolic or political; for them, the desire to compete against the world’s top sportsmen promised personal bests and recognition as successfully embodied masculinity.

Georgetown, thus, started me on a path devoted to a life of the mind, a life that questions basic assumptions about things as natural and self-evident as gender, race, and nation.

Wilson Chacko Jacob is Professor of History at Concordia University. He graduated from Georgetown’s five-year BSFS/MAAS program in 1995 and earned his PhD from New York University. Dr. Jacob is author of Working Out Egypt: Effendi Masculinity and Subject Formation in Colonial Modernity, 1870-1940 (Duke University Press, 2011) and For God or Empire: Sayyid Fadl and the Indian Ocean World (Stanford University Press, 2019).

Lindsey Jones-Renaud

Lindsey Jones-Renaud

MAAS ‘06

It was 2012, and I was in Bnaslawa, a town outside of Erbil in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. I was meeting with a group of community leaders involved in a development project to identify and address priority infrastructure goals, such as constructing new roads or equipping health centers with medical supplies. Although the community groups were entirely Iraqi-led, they were mobilized by the project, which was designed and managed by international and American donors and development practitioners.

The purpose of my meeting was to conduct a “gender assessment”—a development industry term for a type of participatory re-search designed to determine the extent to which a project has integrated principles of gender equity into its activities. In an attempt to be inclusive of women, this particular project required that at least 3 of the 12 community group leaders be women. “This [quota] is not equality,” one woman in the group told me. She added angrily that had it not been for that quota, they would have achieved 50 percent female representation on the board. As I spoke with the other women, it became evident that they understood the quota to indicate there should be a maximum, rather than a minimum, of three women. Clearly, the intended impact of the quota was lost somewhere between the American practitioners who came up with it and the Iraqi women who were supposed to be benefiting from it. This misunderstanding was a stark reminder of how a top-down, one-size-fits-all approach to gender equity and equality that is driven by outside actors doesn’t work. It often causes further harm.

One of the most powerful things I learned during my time in MAAS is the importance of regularly reflecting on my own positionality and power as a white American studying—and later working in—the MENA and other regions around the world that have been directly impacted by my own country’s historical and present actions. I must continue to do that as a development practitioner focused on gender equality, a field in which most of the people deciding funding and program priorities are still, like me, largely from or based in the United States, Europe, and Canada. In my work, I try to focus on pushing for shifts in power and resources to the women and genderqueer-led movements and organizations that are working for gender equity in their own communities so that women like the ones I met in Bnaslawa can determine their own actions for advancing gender equity instead of being forced to follow our misguided ones.

Lindsey Jones-Renaud has been working in the international development sector since she graduated from the MAAS program in 2006. She is the founder, owner, and principal consultant for Cynara Development Services, which provides facilitation, training, social impact analysis and strategic planning services for organizations working to advance gender equality and social justice.

This article was published in the Spring 2020 issue of the CCAS Newsmagazine.