Since the 2014 drop in oil prices, Gulf countries have begun to shift their attention toward renewables.

By Aisha Al-Sarihi

Despite the abundance of oil and gas resources, and decades of high economic dependence on their export revenues, the hydrocarbon-rich Gulf Arab states—Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates—have recently shifted their attention toward renewable energy. Between 2014 and 2018, the total renewable electricity installed capacity in the Gulf Arab states increased by almost 313 percent, according to the International Renewable Energy Agency, an intergovernmental organization that supports countries transitioning to sustainable energy. Dubai’s planned 5,000 megawatt Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum Solar Park, which will be one of the largest solar parks in the world, is just one example of how this shift in governmental priorities is resulting in ambitious renewable energy projects across the Gulf.

Why have the Gulf Arab states experienced such growth in renewable energy over the past five years?

Renewable energy adoption has been promoted around the world as a way to tackle global warming and meet the goals set by the Paris Climate Agreement. Across the Gulf Arab states, however, the main drivers of this new focus on renewables have been the need to keep up with growing domestic oil and gas demands while also increasing exports, and to free up fuel needed for downstream economic diversification projects. Addressing these needs has become even more urgent since 2014, when oil prices plunged by more than 56 percent from a peak of $155 a barrel, leading to reduced oil export revenues and state budget deficits. At the same time, the surge in domestic demand for oil and gas, especially for electricity and water desalination, has posed a serious challenge to pursuing ambitious economic diversification plans, such as downstream oil industries and the production of petrochemicals, which also require oil and gas resources for their operations.

Together, the domestic energy demand and the expansion of diversification projects, have necessitated a search for alternative energy sources including natural gas (both exploration and imports) and renewable energy. However, given the uncertainties associated with new natural gas discoveries and escalating geopolitical tensions with neighboring natural gas-rich states like Qatar and Iran, it makes sense for Gulf Arab states to promote the development of local and more sustainable energy sources.

Furthermore, the significant decline in the cost of renewable energy technologies has enabled Gulf states to develop both small and large-scale renewable energy projects. Over the last decade, the global average levelized cost of electricity (LCOE) from solar panels and onshore wind decreased by 73 percent and 22 percent respectively between 2010 and 2017. In fact, Gulf Arab states have broken global records in terms of the cost of energy produced from renewable energy projects. For example, the LCOE for Saudi Arabia’s first solar project, Sakaka, was 2.34 U.S. cents per kilowatt hour, one of the lowest costs in the world.

Are all six Gulf Arab states progressing equally toward renewable energy adoption?

Although the six Gulf Arab states have all faced the discussed energy-policy challenges, their responses and progress toward renewable energy development vary, falling into the following four categories.

Leading Developer

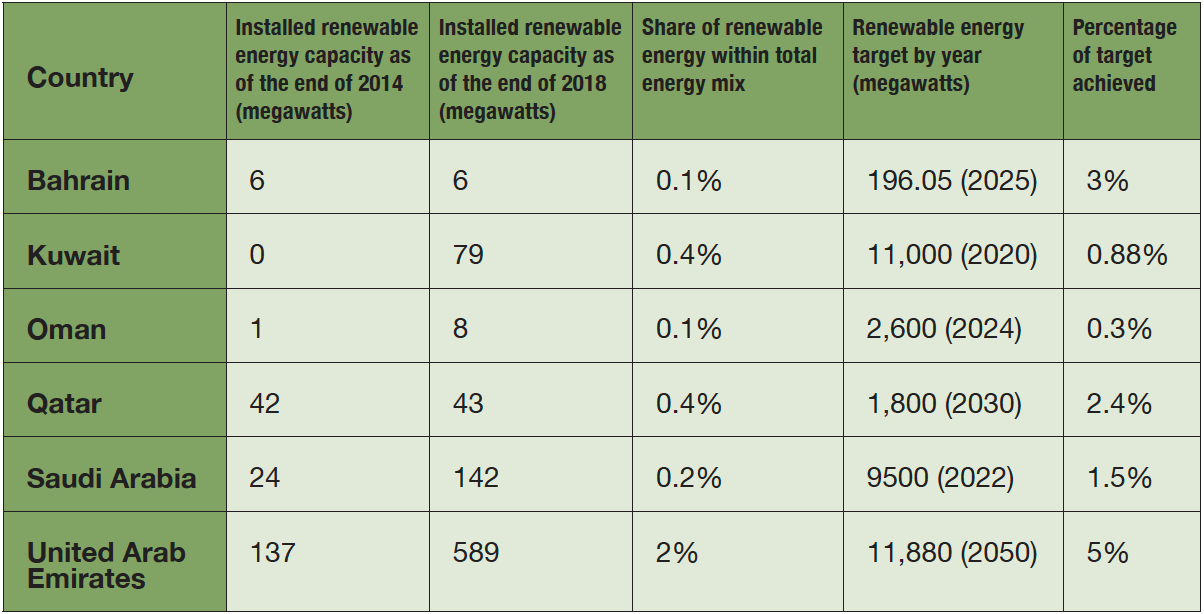

With the largest total installed renewable energy capacity of 589 megawatts (see Table 1), the United Arab Emirates is leading its neighboring countries in terms of renewable energy adoption. The UAE has been proactive in supporting the development of renewables since as early as 2008 when it established Masdar City to foster international knowledge sharing and research collaboration, including with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), and international business partnerships. Renewable energy projects in UAE have also enjoyed the support of political leaders who want to reverse the country’s international reputation of having a high per-capita carbon footprint and the willingness of banks to fund such projects. As a result, UAE has expanded its renewable energy projects by 329.93 percent between 2014 and 2018. UAE has already achieved 5 percent of its goal to source 44 percent of energy production from renewables by 2050.

Stagnant Developers

While Bahrain and Qatar have achieved 3 percent and 2.4 percent, respectively, of their 2050 renewable energy targets (see Table 1), their progress in promoting the adoption of renewable energy has remained stagnant since 2014. Plummeting oil prices that pressured other Gulf countries to expand investment in renewables did not have the same effect on Qatar and Bahrain, neither of which rely on oil export revenues as their major source of income. The abundance of natural gas in Qatar has also meant that the country has little incentive to pursue renewable energy options.

Progressive Developers

Having achieved less than one percent of their renewable energy targets, Oman and Kuwait have shown slow but progressive adoption of renewable energy over the past five years. Both countries were highly impacted by the 2014 drop in oil prices, yet unlike in the UAE, the scope of their international research collaborations and joint ventures have been negligible. Since the technical and financial capacities required for deploying new renewable energy projects have proven challenging for Oman and Kuwait to meet, it has made sense for both countries to adopt a wait-and-see approach. After starting with small pilot projects to learn more about the renewable energy sector’s technical, regulatory and financial challenges, the governments of Oman and Kuwait have gained the confidence to pursue commercial solar roof-top projects and establish international business partnerships. For example, Oman has forged an agreement with Masdar, the Abu Dhabi-based energy company, to fully finance and install a wind farm in the country’s southern district.

Ambitious but reluctant developer

Among the Arab Gulf countries, Saudi Arabia has released the most ambitious but reluctant renewable energy targets. In 2016, the Kingdom set a target to source 9.5 GW of its electricity from renewables by 2023, but this actually represents a scaled back figure from the original target of 54 GW of electricity from renewables by 2040. Similarly, the government has established multiple joint ventures with international partners to facilitate the transfer of renewable-energy technology to Saudi Arabia, but many of these have been terminated before meeting their goals or producing actual renewable energy. Despite the abundance of funding to support renewable energy research initiatives, the Kingdom’s priority to increase oil prices in international markets in order to protect its export revenues has been pushing renewable energy lower on the political and economic agenda. Saudi Arabia’s current renewable energy installed capacity of 142 MW gives little indication that it will be able to meet its ambitious 2023 goal.

Looking forward, will Gulf Arab states continue to reduce dependence on fossil fuels and expand renewables?

The above analysis suggests that the Gulf Arab states’ progress in renewable energy development over the past few years has been strictly linked to oil price fluctuations, and the need to free up oil and gas for export and to fuel growing petrochemical industries. A future of 100 percent reliance on renewables or other non-fossil fuel resources, such as nuclear, is hard to imagine for the Gulf Arab states because profits generated from renewables are unlikely to outweigh those gained from oil and gas exports.

Nonetheless, it is advantageous for Gulf Arab states to maintain momentum in pursuing renewable energy projects and advancing strategies and policy frameworks that support their development. Promoting renewables in the Gulf would not only ease economic vulnerability from fluctuating oil prices and enhance energy security, but also put Gulf states in line with the Paris Climate Agreement goals to cut greenhouse gas emissions and prepare the region to compete in a fossil-fuel constrained future.

Dr. Aisha Al-Sarihi is a Research Associate at King Abdullah Petroleum Studies and Research Center and a Non-Resident Fellow at The Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington. She was a Visiting Researcher at CCAS during the Spring 2019 semester. This article was originally published in the Fall 2019 issue of the CCAS Newsmagazine.