Q&A with Professor Rochelle Davis

CCAS Professor Rochelle Davis’ latest book project examines the role that the U.S. military’s conception of culture played in the American wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Her work—which makes use of interviews with U.S. servicemembers and Iraqis, as well as military documents, cultural training materials, journalist reports, and soldier memoirs—analyzes the narratives that are told about Iraqis, Afghans, Arabs, and Muslims and explicates the paradoxical military objectives of cultural sensitivity and occupation. Professor Davis, who has published two prior books on Palestine, is currently finalizing the manuscript for No Good Way to Occupy a Country. She shares a bit about her project below.

How did you get started on this research?

When I came to teach at Georgetown in 2005, the U.S. occupation was in its third year and CCAS had invited the late Anthony Shadid to speak on his book Night Draws Near: Iraq’s People in the Shadow of America’s War. I recall an American military officer in the audience remarking that “we are trying to do better, we are trying to provide cultural training now.” As an anthropologist whose academic discipline is about culture and society, I was intrigued and wondered about the content of military cultural training. I began going to lectures by civilians who worked for the military about their vision of “cultural training” and collecting material and eventually trained six student research assistants to conduct interviews with veterans and current services members. The research—which includes interviews with 70 U.S. military personnel and 50 Iraqis, plus thousands of pages of written material and videos—grew into a book project, which is now almost completed.

What are some of the takeaways from the book?

First, that so much of the cultural training is mired in Orientalist and/or racist tropes copied and pasted from material that is ten, twenty or seventy years old. For example, the idea that Arabs take offense easily has been baked into military guides across the decades. The 1943 U.S. military’s Short Guide to Iraq issues a warning to take care in not offending locals, as that could undermine the entire mission: “American success or failure in Iraq,” it reads, “may well depend on whether the Iraqis […] like American soldiers or not.” This idea of the offendable Arab gets repeated in a Department of Defense Pocket Guide to the Middle East from 1962 “To avoid offending Arabs, you must observe their customs when you are with them. If you do, you will gain their warm friendship. Since their religious and social customs are closely intermingled, one misstep on your part might violate both.” Fast forward forty years to the American invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan—and soldiers were still receiving similar information. One reported being told in his cultural training: “Instead of shaking hands, use the hand gesture of putting your palm over your heart. Not showing the bottoms of your feet. The type of conduct that would be offensive to an Iraqi you picked up quickly.”

This trope of Arabs taking offense suggests that somehow Arabs are rigid and bound by their own behaviors, and thus are not familiar with other ways of life. The focus on avoiding offence also struck me as misplaced. Perhaps because I saw the invasion of the country (any country) as wrong, the concern that a soldier might do something “offensive” seemed to focus on something trivial, given there was so much American violence toward Iraqis and the discounting of Iraqis’ expertise and knowledge. Suggesting that “causing offense” was what was critical to the occupation missed the point about why some Iraqis were not supportive of the U.S. presence in Iraq. One soldier described how, in his experience with cultural training, the power dynamic was framed almost as if the soldiers were tourists in a host country, and causing offense could result in getting laughed or shouted at or kicked out of a café. “You know,” he recalled learning “here are three or four things that you can do to not offend people. In sort of the same way that you would tell a tourist, which was not really … I don’t think at the depth of what we needed.”

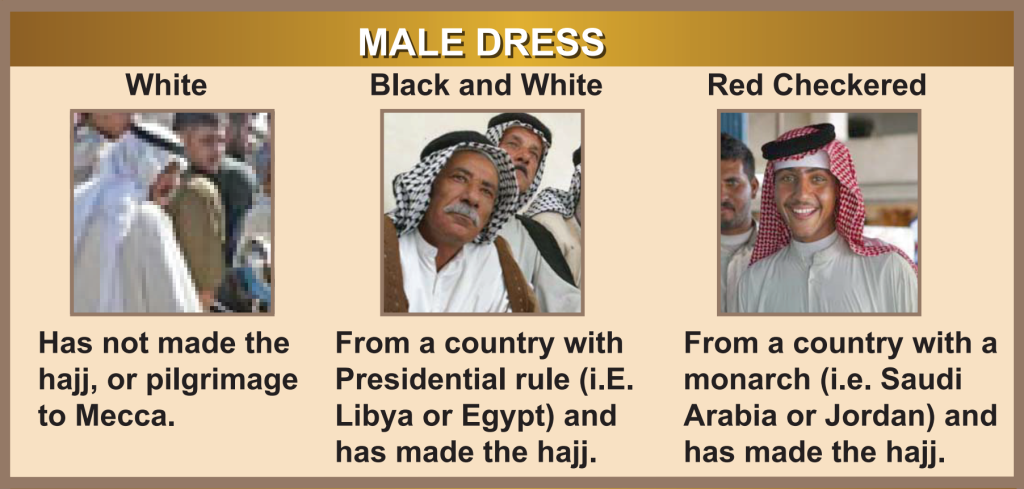

Another example is the simplified depictions of the kufiya. For example, a red and white kufiya, according to the Iraq Culture Smart Card, meant the person was from a country with a monarchy, while black and white indicated he was from a country with presidential rule. A plain white kufiya signified that the wearer had not been on pilgrimage to Mecca. But what did all this have to do with Iraq? Over and over again the cultural training material relied on wrong information and Orientalist stereotypes and failed to demonstrate an understanding of the big picture. Was it racism on the part of the developers? Lack of time? Lack of knowledge? Much of the material lists no author, so it is difficult to probe further.

A second takeaway from the book was how the cultural training was counter to the U.S. government’s stated reasons for the invasion and occupation of Iraq. The examples are many, but a blatant one is that President Bush cited, as one of three reasons for the invasion, the goal of bringing democracy to Iraqis, which many of the soldiers interviewed also gave as the reason they thought they were there. At the same time, the Soldier’s Handbook to Iraq, published by the Army 1st Infantry Division in 2003, declared that Iraqis are essentially unable to practice democracy because of their culture and faith:

“[Their] desire for modernity is contradicted by a desire for tradition (especially Islamic tradition, since Islam is the one area free of Western identification and influence). Desiring democracy and modernization immediately is a good example of what a Westerner might view as an Arab’s ‘wish vs. reality.’”

In other words, American soldiers being sent to invade and occupy Iraq to free its citizens were being told that Iraqis were not ready for democracy. This is despite the fact that Iraqis were on the street demonstrating for elections to be held after Paul Bremmer cancelled them in June 2003.

In presenting my research, I’ve had a number of military contractors and personnel ask me how I would recommend it be done differently. My response is always: “I’d start by not invading other countries”—hence the title of my book. I know that military personnel don’t have a choice. They have to obey their orders. Could the cultural training have been better? Certainly. Would it have changed the outcome? Unlikely. The most damaging impacts of the occupation resulted not from the types of surface-level, cultural interactions covered in the training materials. They resulted instead from policies that created sectarian political representation, postponed elections, and disbanded the Iraqi military and police—to name but a few.

Associate Professor Dr. Rochelle Davis is the Director of Graduate Studies and holds the Sultanate of Oman Chair at CCAS.

This article was originally published in the Spring/Summer 2023 CCAS Newsmagazine.