Passing storm, opportunity for change, or regional catastrophe?*

By Haizam Amirah-Fernández (MAAS ’01)

See note at end to learn about the artists featured here.

The COVID-19 pandemic is shaking Arab countries hard at a time when the region is already under great pressure. The responses of Arab states to the threat of the coronavirus, added to the uncertain international context generated by the pandemic, is aggravating existing problems in the Middle East and the Maghreb. This current global emergency and its ramifications has the potential to turn socioeconomic challenges into political crises and intensify demands for change that have spread through multiple countries in the region over the past decade. Until an effective vaccine against the pandemic is made available and widely accessible, the economic and social costs of the drastic restrictions being imposed by Arab governments during the successive waves of the pandemic may be overwhelming and, ultimately, unbearable.

An aggravating factor for existing problems

For rentier economies that depend on income generated by the sale of hydrocarbons, the fall of oil prices in the middle of a pandemic poses a major problem for their public accounts. This directly affects not only energy producers in the Gulf, but also Algeria. Starting in February 2019, Algeria experienced widespread social mobilizations (known as hirak) that were unprecedented in terms of their duration (56 consecutive weeks) and the civic attitudes shown by the demonstrators. The demonstrations were suspended in March 2020 due to the increase in cases of COVID-19 and to avoid the risk of infection in a country with poor health infrastructure.

There is a widespread feeling in Algeria that the political system is sclerotic and that building a civil state marked by the separation of powers and good governance will require profound reforms. When Algeria’s rulers were benefitting from high revenues from the sale of hydrocarbons, they could afford to buy social peace with subsidies and grants. However, with the sharp fall in revenues this year, along with the worrying decline in foreign exchange reserves, the outlook for Algeria over the next few years is far from reassuring. Moreover, Algerian President Abdelmadjid Tebboune contracted COVID-19 in October, ten months after winning a dubious presidential election, and had to be flown to Germany to receive medical treatment. The referendum for a new constitution that he promoted was held while he was away from the country. The final result—with only 13.7% of registered voters supporting the new constitution—further exposed the regime’s deepening legitimacy crisis, even as difficulties posed by the pandemic and other factors continue to grow.

Morocco is also facing a significant drop in revenues, the extent of which remains unknown. Morocco’s High Commissioner for Planning declared in March that 2020 would be the worst year for the Moroccan economy since 1999. In addition to the sharp decline in tourism, the global recession could significantly reduce the remittances sent by Moroccans working abroad, mainly in Europe, which previously accounted for more than six percent of Morocco’s GDP. On the other hand, the significant fall in internal and external demand for goods and tourism, the extent of which will depend on factors beyond the control of the Moroccan authorities, has been compounded by a drop in agricultural production due to the drought that began in 2019. Against this backdrop, it is foreseeable that recent signs of social discontent caused by a lack of opportunities, economic inequalities, and disparities between regions will increase.

For Tunisia, the COVID-19 pandemic is the first major test for the government that formed in February, following the elections held in October 2019. This Maghrebi country—and the only democracy in the Arab region—suffers from persistent economic problems that the pandemic is now exacerbating. The problems stem from a drop in tourism income (typically around 12% of Tunisia’s GDP) and decreased trade with Europe. The Tunisian government, like that of Morocco and others in the region, launched campaigns asking for donations from the population to meet the expenses that the state could not cover in the fight against the coronavirus.

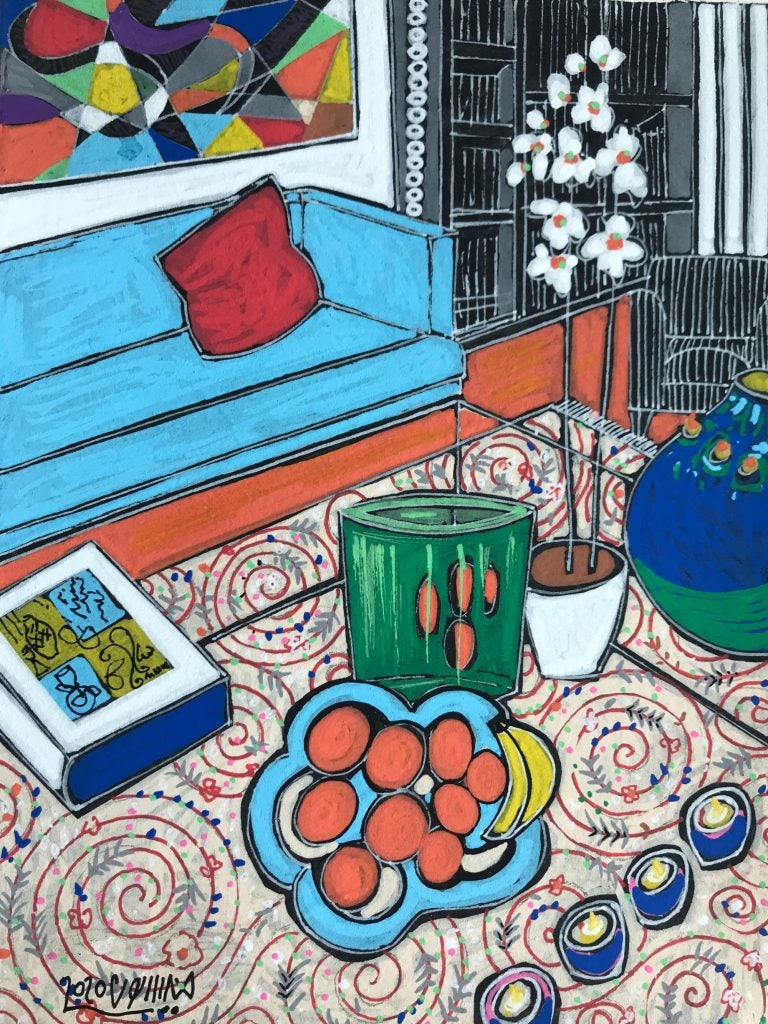

Worry, 2020

Pastel on paper

Courtesy of the artist

Since October 2019, both Iraq and Lebanon have experienced demonstrations calling for an end to corruption and for the states to fulfill their most basic functions. The multiple failures of these governments and the absence of legitimate political leaders with the capacity to resolve the enormous problems emerging from systems long corroded by sectarianism have only further deteriorated with the arrival of the pandemic. Iraq is suffering from a sharp drop in oil revenues, caused in part by the price war started by Saudi Arabia in March. Meanwhile, Lebanon is facing multiple simultaneous, deep crises, starting with the banking crisis that led the country to announce on March 7 the first sovereign debt default in its history. The severe devaluation of the Lebanese pound—a loss of nearly 80% of its value against the U.S. dollar since October 2019—and the shortage of foreign currency in a heavily dollarized economy are leading to business closures, job losses, hyperinflation, and major difficulties in importing basic goods, including medical and health supplies. The situation was already on the verge of a catastrophe before the outbreak of the COVID-19 crisis and has only been worsened by the massive explosion in the port of Beirut in August, which caused enormous human and physical devastation.

Syria, Yemen, and Libya are all in the throes of armed conflict, each one subject to external interference fueling their civil wars. It is striking that these three countries have each declared shockingly low numbers of coronavirus infections. While it is true that the dangers of travel in these countries may have reduced the spread of the virus, their low reporting figures are most likely due to low testing levels as well as to the withholding of information. The consequences of outbreaks in these countries would be devastating, especially for the millions of people and internally displaced persons who lack healthcare and means of prevention. Even with international assistance, it would be difficult to contain the virus if complex emergencies occur in conflict areas or in refugee camps in neighboring countries.

Egypt, which is the most populous country in the region (home to a quarter of the total Arab population), has recorded one of the highest numbers of infections among Arab countries. However, given the regime’s past records, there is no guarantee of the accuracy of the official data. The economic impact of the pandemic in Egypt is reflected in its drop in tourism revenues, the decline in maritime traffic through the Suez Canal, and the reduction in remittances sent by Egyptians from oil-producing countries—each of which is crucial to the much-needed inflow of foreign currency and direct investment.

Jordan set a successful example of combating COVID-19 during the first wave of the pandemic (March-September 2020) through a combination of strict closures and restrictions. However, the serious blow this dealt to the already reeling Jordanian economy has since lead both the government and the public to neglect earlier, successful health measures in order to keep some economic sectors alive. As with other countries in the Arab region and beyond, Jordan has seen the numbers of infections and deaths soar during the fall of 2020. The pandemic has only intensified Jordan’s socioeconomic challenges and institutional malaise—and all within the context of growing regional shifts that are undermining Jordan’s geopolitical importance.

The COVID-19 global crisis is also highlighting the interdependence between the populations and economies of Israel and Palestine. The spread of the coronavirus forced the leaders of Israel, the Palestinian Authority, and Hamas to cooperate with each other during the pandemic’s first wave in order to prevent large-scale infections in Israel, the West Bank, and Gaza. One indication of the exceptionality of this cooperation is that the Israeli government allowed tens of thousands of Palestinian workers from the West Bank to settle on Israeli territory—something that was previously forbidden—for the duration of the health emergency to reduce the spread of infection. The risk of an outbreak is most worrying in Gaza, one of the most densely populated territories in the world. As a result of the Israeli blockade, mismanagement by Hamas’s local government, and the devastation left by three wars with Israel between 2008 and 2014, Gaza also lacks the health infrastructure, water, and electricity needed to support its 1.8 million inhabitants.

The six members of the Gulf Cooperation Council—Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates—have greater resources and more efficient health systems than the rest of the region. However, economic turbulence and the fall in oil prices have put pressure on their finances and public services as well. Virtually all GCC countries have implemented extensive restrictive measures to contain the spread of the pandemic. Even so, the risk of infection among foreign workers—in some Arab Gulf countries they make up the majority of the population—is high, especially among those working in the key construction and service sectors, who are more likely to live in overcrowded conditions without access to good health services.

Home #21, 2020

Acrylic on paper

Courtesy of the artist

The pandemic has greatly impacted not only the tourism, international transport, and real-estate sectors in the Arab Gulf countries, but also major international events that were planned to take place in the region, such as Dubai’s Expo 2020, which had to be postponed for one year. Likewise, the COVID-19 pandemic dealt a blow to Saudi Arabia’s ambitions during its G-20 presidency. The Crown Prince had hoped to rehabilitate the country’s image on the international stage and focus on its plans to open up the Kingdom and diversify its economy. Instead, the activities and the closing summit of the G-20 were mostly virtual, and the presidency faced unprecedented challenges that made it difficult to successfully perform its functions.

Opportunities in the time of COVID-19

Arab countries are missing an opportunity to overcome their political divisions and to instead cooperate in the fight against regional spread of the coronavirus. However, it is not too late to initiate coordination within the region, or to launch initiatives for cooperation and mutual support at the material, technical, and financial levels. This is a unique opportunity for the Arab League, on the 75th anniversary of its founding, to demonstrate its usefulness by doing more than just issuing communiqués. The public health emergency should also serve to reactivate sub-regional initiatives like the Arab Maghreb Union, which was founded in 1989 to promote cooperation and integration among five Arab states of North Africa but is now in a state of semi-hibernation.

There is also an opportunity to change the basis of international cooperation between regions that are likely to be hit hard by the global recession. The European Union should start thinking—even before the health emergency has passed—about ways to revive Euro-Mediterranean cooperation, coinciding with the 25th anniversary of the Barcelona Process. Major efforts and resources will be required for post-pandemic reconstruction on both shores of the Mediterranean. Now is the time for the Union for the Mediterranean to prove whether it can, with the support of other multilateral development institutions, pull the region out of a serious multidimensional crisis. Failing to do so will certify its irrelevance.

Over the past decade, the Arab region has been experiencing mobilizations and revolts against several of its regimes due to their economic failures, inefficient management, corrupt practices, and authoritarian methods. The two waves of the Arab uprisings (2011 and 2019), which swept through most Arab countries, were propelled by the erosion of economic security and the deterioration of social protection systems. In some countries, the pandemic may further undermine what little economic security remains and dismantle the social protection systems that are still in place. Undoubtedly though, this same pandemic offers an opportunity to negotiate new social contracts in Arab countries at a time when the coronavirus has put most anti-regime protests on hold. For the moment, however, there are no signs that this is happening.

The final outcome of the COVID-19 crisis for Arab countries will be conditioned by several factors: the duration of the international health emergency, the effectiveness of state policies—where they exist—in mitigating the pandemic’s health and socio-economic consequences, and the perceptions that citizens hold of how their rulers managed the crisis. And yet, many of the factors that will condition the way out of this crisis are beyond the control of Arab governments, as they too are impacted by rapidly changing global dynamics that, in turn, determine many of their sources of income—hydrocarbons, trade, tourism, transport—and the employment opportunities that their young populations may find.

* A longer version of this report was originally published in Spanish by the Elcano Royal Institute on March 31, 2020 (available here).

Haizam Amirah-Fernández is a Senior Analyst for the Mediterranean and Arab World at Elcano Royal Institute in Madrid and Associate Professor of International Relations at IE University. He graduated from the MAAS program in 2001. You can find more of his work on Twitter: @HaizamAmirah

About the Artists

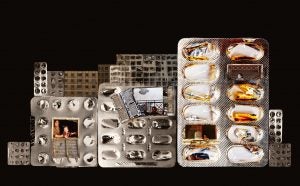

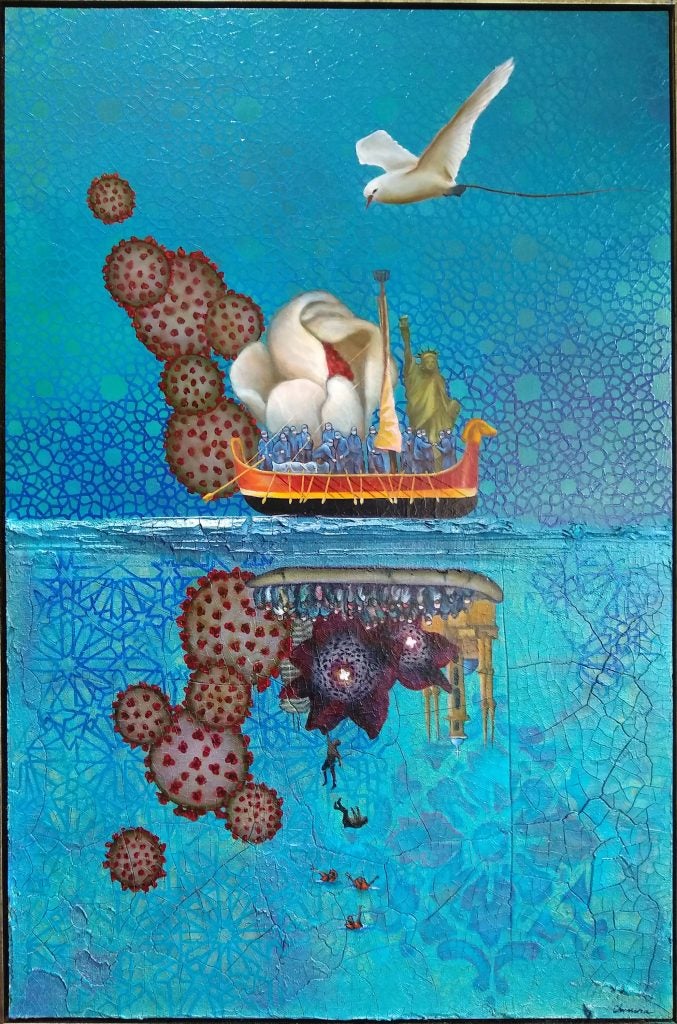

The art illustrating this article is part of the exhibit “Art in Isolation: Creativity in the Time of Covid-19” at the Middle East Institute, which was curated by MAAS student Laila Jadallah. You can read about her role here. All works in the exhibit are for sale, with proceeds going to the artists.

Artist, curator and conservationist Melissa Chimera is a Honolulu native of Lebanese and Filipino descent. Her work investigates globalization, human migration, and species extinction. Chimera studied natural resources management at the University of Hawai‘i and worked for two decades as a conservation manager. Her most recent project is The Far Shore: Navigating Homelands for the Arab American National Museum in Dearborn, Michigan (2018). The exhibition commemorates the 100th anniversary of the end of the Great War and concerns the contemporary issue of Arab immigration to America. Chimera is the recipient of the Catherine E. B. Cox Award from the Honolulu Museum of Art. She has exhibited internationally and her work resides in the collections of the Arab American National Museum, MI; the Honolulu Museum of Art, HI; and the Hawai’i State Foundation of Culture and the Arts, HI.

Maysaloun Faraj is an Iraqi-American painter, sculptor and curator living in London. Displaced by decades of war, Faraj creates work that is deeply rooted in her personal connection to Iraq, the intersection of place and identity, and overarching societal concerns. Faraj received a B.S. in Architecture from the University of Baghdad (1978) and studied ceramic sculpture at Putney School of Art and Design. Faraj was also a resident artist at the Cité Internationale des Arts, Paris (2015-2018). Her artistic career spans four decades and she has become an integral figure in the rise of contemporary Middle Eastern art, curating Strokes of Genius, the first international exhibition of Iraqi modern art which toured internationally (2000-3) and co-founded Aya Gallery, London to advance art from Iraq and the Middle East. Her work is in many major institutions, including The British Museum, London; National Museum for Women in the Arts, Washington, DC; and the Barjeel Foundation, Sharjah.

Jamila Rizgalla is a self-taught Libyan artist who works in pastel to achieve quick, emotive compositions. Rizgalla has participated in several exhibitions in Libya and Malta, recently Take us on your journey through quarantine at Art House, Libya (2020) and Wings of my Soul at Manoel Theatre, Malta (2008). Her work is featured in collections internationally, including Tempra Museum for Contemporary Art, Malta; Museo Tempra della Biennale de Malta, Italy; Museo della Grafica, Italy; and Istituto Italiano di Cultura, Libya. In addition to her visual arts practice, Rizgalla is a veterinarian by education and is currently a lecturer in the Department of Aquaculture at the University of Tripoli.