Two renowned professors of history at CCAS discuss why studying the contemporary Arab world requires thoughtful examination of the past.

By Judith Tucker and Mustafa Aksakal

Almost a decade ago, MAAS faculty from across disciplines began to notice, in their teaching about politics, economics, society, and culture, that many of our students came to the study of the contemporary Arab World with a limited sense of the genealogies of the challenges facing the region today. They felt that, while the Arab people, like all people, are not hapless victims of the past, those studying the region cannot afford to ignore the ways in which the world today has been shaped by complex forces of history, especially since these forces—for better and for worse—can both expand and circumscribe present possibilities, as well as the ability to imagine different futures. In seeking ways to help our students develop thinking about current issues that bring the richness of historical context to bear, MAAS faculty designed the historical survey course ARST 500 and launched it in 2014. We created the course not only to challenge simplistic “presentism,” whereby the past is viewed solely through the distorting lens of contemporary concerns and projects, but also to study history as a path to analyzing the deep roots of the issues we confront in the world today—many of which originated in former times when different political arrangements and world views held sway.

The vitality of women’s movements, and the striking presence of women in the protests and uprisings of recent years, provide a timely example of how knowledge of history can help us explore the present. The power women exercise in public spaces, and the backlash that can result, are both part of a longer history of ambivalence about women’s political roles. In the Arab world, women’s movements developed in the twinned context of colonialism and anti-colonial nationalism. Women pursuing greater freedoms had to avoid any appearance of being divisive and often struggled for their own liberation through nationalist channels, which were considered “honorable” and also aligned with their own support for the nationalist cause. They also had to distinguish their goals from those of colonialist overlords who legitimized their control by claiming the mantle of protector of native women’s liberation, even as they allied with the more conservative elites in local society.

Many women’s movements in Syria and elsewhere began in a lowkey fashion as charitable endeavors that served the needs of society. Even though the women involved were expanding their traditional activities, they were doing so within their accepted role as family nurturers and in ways that served the nation. Thus, the argument for women’s rights – for education, public roles, fair treatment—were usually couched in terms of the collective good, that is, in the interests of the family, the community, and the nation. To better understand this fraught relationship between feminism and nationalism, one of the texts we read in ARST 500 is Elizabeth Thompson’s book, Colonial Citizens: Republican Rights, Paternal Privilege, and Gender in French Syria and Lebanon. Thompson leads us through the colonial period in Syria, showing how women thought and acted as they maneuvered between colonial powers and the conservative forces in their society, and how they were deserted by their nationalist male allies in the process. Through her work and others, we see how women in the Arab world, long accustomed to dealing with complex political landscapes, developed their own approaches and strategies for expanding beyond their traditional roles that were adapted to the context of their times yet left traces we can still see today.

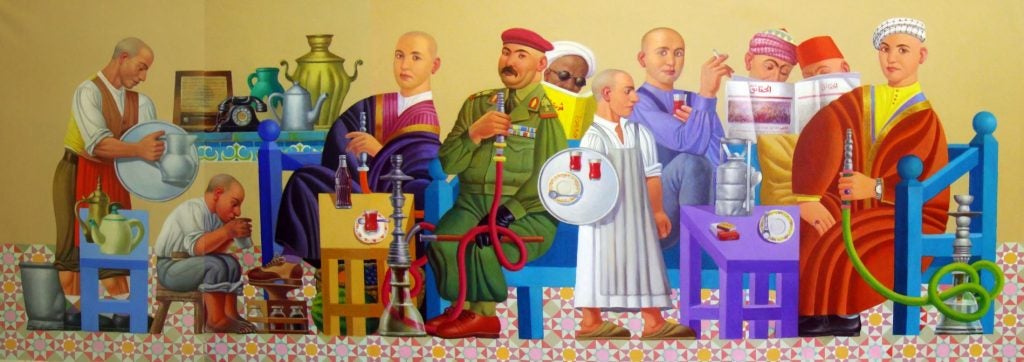

The Kobra Qasr al-Nil, built in Cairo in 1872, depicts the famous Egyptian politician Saad Zaghloul. Avedissian’s portrayal “speaks to how statues and monuments are built for purposes of creating national narratives,” says Prof. Tucker.

The importance of attending to the past is brought home even more forcefully, perhaps, by studying historical narratives themselves, and how they change over time. The stories people tell—or are told—about their histories are deeply shaped not only by the past but also by the exigencies and agendas of their own times. In ARST 500, we read Yoav Di-Capua’s Gatekeepers of the Arab Past: Historians and History Writing in Twentieth-Century Egypt and Eric Davis’ Memories of State: Politics, History, and Collective Identity in Modern Iraq to help us trace the development of national historical narratives under the Arab socialist regimes of Egypt, and the Qasim and Ba`thi regimes in Iraq, respectively. In our discussions of these texts, we ask: What did it take to rewrite history and to alter historical memory, on both intellectual and practical levels, in Egypt and Iraq? What kinds of institutions, education, and performances were central to this task? We find that the standard narratives, which had long held sway in these countries, were refashioned to celebrate revolutionary times and the regimes in power. This refashioning was done through a number of modalities. New forms of public display—ceremonies, holidays, festivals, and commemorations—enacted history as revolutionary triumph. There were erasures and replacements: statues of past leaders were removed, and history texts were rewritten. In 1960s Egypt, the idea of committed history triumphed as the revolutionary moment called for historians to direct their attention to social and economic narratives that privileged the agency of peasants and workers. In Iraq, the Ba`thist regime sponsored archeological projects, conferences, and festivals that promoted an inclusive Iraqi nationalism while also forwarding the state’s ambitions to lead the Arab world. Tracing the twists and turns of these narratives allows us to reflect on the centrality of historical memory to state legitimacy and national identity, both in the past and in the present, and to bring our critical faculties to bear on historical narratives wherever we find them.

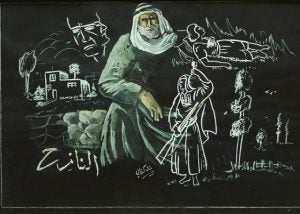

Another ARST 500 reading, The Commander: Fawzi al-Qawuqji and the Fight for Arab Independence 1914-1948 by Laila Parsons, provides—through the example of Fawzi al-Qawuqji’s life and career spanning the late Ottoman period to the Anglo-French colonial mandates in Syria and Palestine—a compelling illustration of how seemingly-ironclad ideologies and fixed viewpoints can evolve and even change drastically over a relatively short period of time. Parsons’s account asks readers to approach critically the use of personal memoirs and archival material and draws attention to unspoken assumptions that so often undergird historiographical consensus. Marie Grace Brown’s Khartoum at Night: Fashion and Body Politics in Imperial Sudan, moreover, shows how historical voices, actions, and emotions can be reconstructed, even in the absence of extensive written records. Struggle and Survival in the Modern Middle East and North Africa, edited by Edmund Burke III and David Yaghoubian, also endeavors to tell the story of the lived experience—although here the method of recovering this history is to follow the individual rather than the collective actions of a group.

Brown’s book, much like the volume Is there a Middle East? The Evolution of a Geopolitical Concept (edited by Michael E. Bonine, Abbas Amanat, and Michael Ezekiel Gasper), serves as a crucial reminder of the need to conceptualize the MENA as a region, to reflect on its various parts and the historical forces linking them—from the Maghreb to the Gulf—and to uncover the various paths of convergence and divergence that have molded the region into what it is today. We hope that ARST 500 has challenged students to question both dominant nationalist and Eurocentric accounts, to historicize familiar categories such as ethnic and religious labels, and to recognize the fluidity and changing character of identities, gender roles, and cultural practices.

Dr. Judith Tucker is Professor Emerita at CCAS and the Department of History. Dr. Mustafa Aksakal is an Associate Professor in the Department of History and a CCAS Affiliated Faculty.